“Et huiusmodi stantiae usus est fere in omnibus cantionibus suis

Arnaldus Danielis et nos eum secuti sumus.”

Dante, De Vulgari Eloquio, II. 10.Ah! red-leafed time hath driven out the rose

And crimson dew is fallen on the leaf

Ere ever yet the cold white wheat be sown

That hideth all earth’s green and sere and red;

The Moon-flower’s fallen and the branch is bare,

Holding no honey for the starry bees;

The Maiden turns to her dark lord’s demesne.

So opens “The Yearly Slain,” the first of Pound’s Canzoni, published in 1911. Pound wrote “The Yearly Slain” in response to the Australian poet and novelist Frederic Manning’s “Korè,” published the year prior. In the pre-war years Manning moved to London, where he began lasting friendships with a diverse artistic circle including everyone from Richard Aldington to Max Beerbohm to William Rothenstein and, of course, Pound. (If you were alive in the first half of the 20th century, you probably had a correspondence with Ezra Pound.)

Manning’s poem begins:

Yea, she hath passed hereby, and blessed the sheaves,

And the great garths, and stacks, and quiet farms,

And all the tawny, and the crimson leaves.

Yea, she hath passed with poppies in her arms,

Under the star of dusk, through stealing mist,

And blessed the earth, and gone, while no man wist.

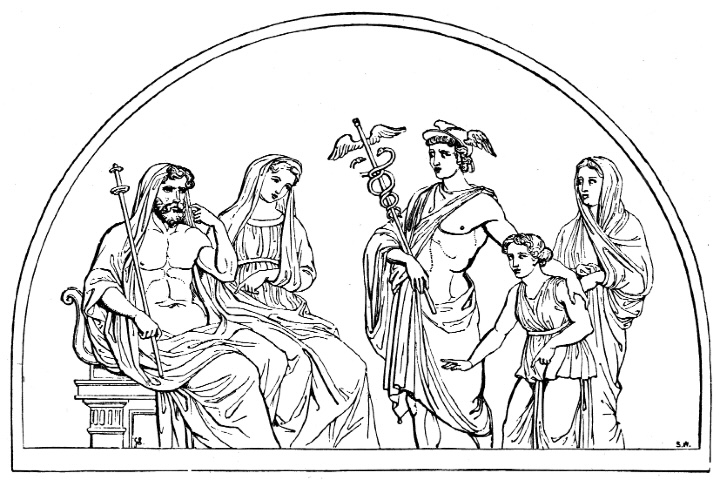

Both Pound and Manning’s poems take as their basis the story of Persephone (aka Korè aka Cora aka “maiden”), daughter of Demeter (aka Ceres to you Romans) and queen of the underworld upon her kidnapping by old Uncle Hades. After Persephone’s abduction the heartbroken Demeter, goddess of corn, allows the land to go barren in her despair. Zeus orders Hades to return Persephone, but after eating the food of the underworld she must forever divide her time between the two realms. The fallow periods born of Demeter’s grief were offered as an explanation for the seasonal cycle. Ancient Greek women honored Demeter and Persephone with the annual fertility festival of the Thesmophoria (parodied in Aristophanes’ comedy Thesmophoriazusae). For the full story, look no further than the Homeric “Hymn to Demeter.”

Fairer than Enna’s field when Ceres sows

The stars of hyacinth and puts off grief,

Fairer than petals on May morning blown

Through apple-orchards where the sun hath shed

His brighter petals down to make them fair;

Fairer than these the Poppy-crowned One flees,

And Joy goes weeping in her scarlet train.

Pound lifts his canzone’s ABCDEF rhyme scheme from the Provençal troubadour Arnaut Daniel, whom he declared the greatest poet to ever live. (Pound quotes Dante, who called Daniel il miglior fabbro, in the epigraph which opens “The Yearly Slain.” Petrarch went so far as to call Daniel the gran maestro d’amore; what a title!) Read aloud in sequence, the rhyme scheme gives the poem a strong musical feel, emphasizing the canzone’s historical role as the song of the troubadours.

With slow, reluctant feet, and weary eyes,

And eye-lids heavy with the coming sleep,

With small breasts lifted up in stress of sighs,

She passed, as shadows pass, among the sheep;

While the earth dreamed, and only I was ware

Of that faint fragrance blown from her soft hair.

Manning’s poem takes for its form a comparatively simple ABABCC scheme, but its content offers the central metaphor for Pound to expand. The use of korè and its more generalized meaning of “maiden” allows both poets to set the classical myth against the broader field of romantic loss and longing, turning Demeter’s daughter into an amphibological lover and the barren fields into a symbol for the sorrow of solitude.

The faint damp wind that, ere the even, blows

Piling the west with many a tawny sheaf,

Then when the last glad wavering hours are mown

Sigheth and dies because the day is sped;

This wind is like her and the listless air

Wherewith she goeth by beneath the trees,

The trees that mock her with their scarlet stain.

The land lay steeped in peace of silent dreams;

There was no sound amid the sacred boughs.

Nor any mournful music in her streams:

Only I saw the shadow on her brows,

Only I knew her for the yearly slain,

And wept, and weep until she come again.

Love that is born of Time and comes and goes!

Love that doth hold all noble hearts in fief!

As red leaves follow where the wind hath flown,

So all men follow Love when Love is dead.

O Fate of Wind! O Wind that cannot spare,

But drivest out the Maid, and pourest lees

Of all thy crimson on the wold again,

In his 1919 essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” Eliot asserts a poet cannot rely simply on his understanding of “the pastness of the past” but on “its presence; the historical sense compels a man to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with […] the whole of the literature from Europe to Homer.” One year prior to “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” Eliot wrote in his “A Note on Ezra Pound” that

A large part of the poet’s “inspiration” must come from his knowledge of history. I mean history widely taken; any cultivation of the historical sense, of perception of our position relative to the past, and in particular of the poet’s relation to poets of the past. Mr. Pound’s extensive knowledge of literature is one important thing, his particular passion for a minute knowledge of Provençal is another. What has mattered is not simply that he has by insight and labour got the spirit of Provençal, or of Chinese, or of Anglo-Saxon, as the case may be; but that he has made masterpieces, some of translation, some of re-creation, by his perception of the relation of these periods and languages to the present, of what they have that we want; and this perception of relation involves an organized view of the whole course of European poetry from Homer.

Manning may not have been quite the miglior fabbro Pound was (Eliot would even repeat the title in dedicating The Waste Land to their mutual friend), but he nonetheless possessed a keen historical sense; his poem bearing Korè’s name as its title was not the only one he wrote in her spirit. Check out “The Faun,” from Eidola:

Kore, O Kore, where art thou fled,

Now that the spring blows white in the land?

Shake out the honeyed locks o’ thine head;

Plunder the lilies that lie to thine hand,

Glistering saffron loved of the bees

Murmuring in them, till shadows grow long

With dew-dropping silence under the trees,

Ere break the voluptuous thrillings of song

From the brown-throated sweet harbourers there

Raptured and grieving under the stars…

In the preface to his 1873 The Renaissance, Pound’s favorite 19th-century critic Walter Pater advances his concept of the virtù of a work of art:

…the picture, the landscape, the engaging personality in life or in a book, La Gioconda, the hills of Carrara, Pico of Mirandola, are valuable for their virtues, as we say, in speaking of a herb, a wine, a gem; for the property each has of affecting one with a special, a unique, impression of pleasure. Our education becomes complete in proportion as our susceptibility to these impressions increase in depth and variety. And the function of the aesthetic critic is to distinguish, to analyse, and separate from its adjuncts, the virtue by which a picture, a landscape, a fair personality in life or in a book, produces this special impression of beauty or pleasure, to indicate what the source of that impression is, and under what conditions it is experienced. His end is reached when he has disengaged that virtue.

Korè my heart is, let it stand sans gloze!

Love’s pain is long, and lo, love’s joy is brief!

My heart erst alway sweet is bitter grown;

As crimson ruleth in the good green’s stead,

So grief hath taken all mine old joy’s share

And driven forth my solace and all ease

Where pleasure bows to all-usurping pain.

“Art is a fluid moving above or over the minds of men,” wrote Pound in the preface to his 1910 The Spirit of Romance. “Art or an art is not unlike a river, in that it is perturbed at times by the quality of the river bed, but it is in a way independent of that bed. The color of the water depends upon the substance of the bed and banks immediately preceding. Stationary objects are reflected, but the quality of motion is of the river.” For Pound, poetry and criticism are vehicles for communicating an eternal virtù, hence his continuation of Manning’s riff on Persephone and Demeter.

Crimson the hearth where one last ember glows!

My heart’s new winter hath no such relief,

Nor thought of Spring whose blossom he hath known

Hath turned him back where Spring is banished.

Barren the heart and dead the fires there,

Blow! O ye ashes, where the winds shall please,

But cry, “Love also is the Yearly Slain.”

In “I Gather the Limbs of Osiris,” Pound offers a sort of indirect justification for borrowing Manning’s take on Greek myth:

The soul of each man is compounded of all the elements of the cosmos of souls, but in each soul there is some one element which predominates, which is in some peculiar and intense way the quality or virtù of the individual; in no two souls is this the same. It is by reason of this virtù that a given work of art persists. It is by reason of this virtù that we have one Catullus, one Villon; by reason of it that no amount of technical cleverness can produce a work having the same charm as the original, not though all progress in art is, in so great degree a progress through imitation.

“This virtue is not a ‘point of view,’” Pound concludes,

nor an ‘attitude toward life’; nor is it the mental calibre or ‘a way of thinking,’ but something more substantial which influences all these. We may as well agree, at this point, that we do not all of us think in at all the same sort of way or by the same sort of implements. Making a rough and incomplete category from personal experience I can say that certain people think with words, certain with, or in, objects; others realise nothing until they have pictured it; others progress by diagrams like those of the geometricians; some think, or construct, in rhythm, or by rhythms and sound; others, the unfortunate, move by words disconnected from the objects to which they might correspond, or more unfortunate still in blocks and clichés of words; some, favoured of Apollo, in words that hover above and cling close to the things they mean. And all these different sorts of people have most appalling difficulty in understanding each other.

Pound closes by sending his canzon floating down the river of art “moving above or over the minds of men”:

Be sped, my Canzon, through the bitter air!

To him who speaketh words as fair as these,

Say that I also know the “Yearly Slain.”

Leave a Reply