Blink and you’ll miss the moment Saint Laurent’s titular protagonist gives the only moment of historical contextualizing on which so many biopics are built. Saint Laurent reminisces on his mother’s parties, “and their dresses, so 1940s,” and in that fragment gives the audience all we’ll receive of the history behind Saint Laurent’s “Hommage aux Annees 40s,” which in 1971 — before Gautier, the Antwerp Six, or Margiela — scandalized audiences by collaging together materials from men’s jackets to gaudy upholstery in vivid pop art compositions. Bonello doesn’t bother with the banal montages and tedious diatribes psychologizing the artistic process endemic to the stale genre of the biopic.

Instead, Bonello and costumer designer Anaïs Romand reenact in lavish detail the collection itself, working in direct opposition to Pierre Bergé, co-founder of Yves Saint Laurent (the fashion label), onetime lover of Yves Saint Laurent (the fashion designer) and backer of Yves Saint Laurent (Jalil Lespert’s blandly conventional biopic released by the Weinstein Company opposite Bonello’s take on the label’s history). Lespert’s film was buoyed by Bergé’s foundation’s cooperation, which included the use of “77 vintage outfits from its archives and [allowing] Lespert to film certain scenes at its headquarters on Avenue Marceau in Paris.” For Bonello’s film, Romand worked without any access to the YSL archive, painstakingly recreating each design from modern materials. The approach calls to mind a very different designer: Vivienne Westwood, who once pointed out her historical recreations — in particular the robe à la Française she lifted from François Boucher’s 1759 portrait of Madame de Pompadour for her Autumn/Winter 1995 collection “Vive la Cocotte” — were by default modern, owing to the fact they required the use of contemporary materials in their construction. For his film, Bonello strikes a similar balance outside of time: the director stages the models in the designer’s clothes descending marble stairs to mingle among the Parisian social elite. No explicit conflict introduces itself, and yet unimaginable stakes imprint themselves on the viewer. Something happens here. The clothes generate an affect, forcing us to look at them with fresh eyes: the designs, in their breaks from convention, appear attractive, audacious, or awkward, and each new ensemble advances an attitude or a worldview, some new species of woman heretofore unknown.

Like Pialat’s Van Gogh or Watkins’ Edvard Munch, Bonello locates and centers the artistry in the artist’s biopic, a creative move which sounds thuddingly, boneheadedly simple until we remember how few films manage the same radical courage of conviction in a sea of Bohemian Rhapsodies and Imitation Games. By presenting the historical materials of the story so directly Bonello erases the diachronic distance between subject and audience.

“It’s completely my way to work” says a voice backstage. “The fragments of the past, for me, are not without life.” But though the words might just as easily have been Saint Laurent explaining Saint Laurent as Bonello explaining Saint Laurent, the preceding quote comes from Alessandro Michele, former creative director of Gucci (and now Valentino) discussing his Autumn/Winter 2016 collection, “Rhizomatic Scores.” Deleuze and Guattari’s influence may seem an unlikely one on the design house who under Michele’s predecessor Tom Ford built their reputation on as simple a running theme as could be imagined: sex.

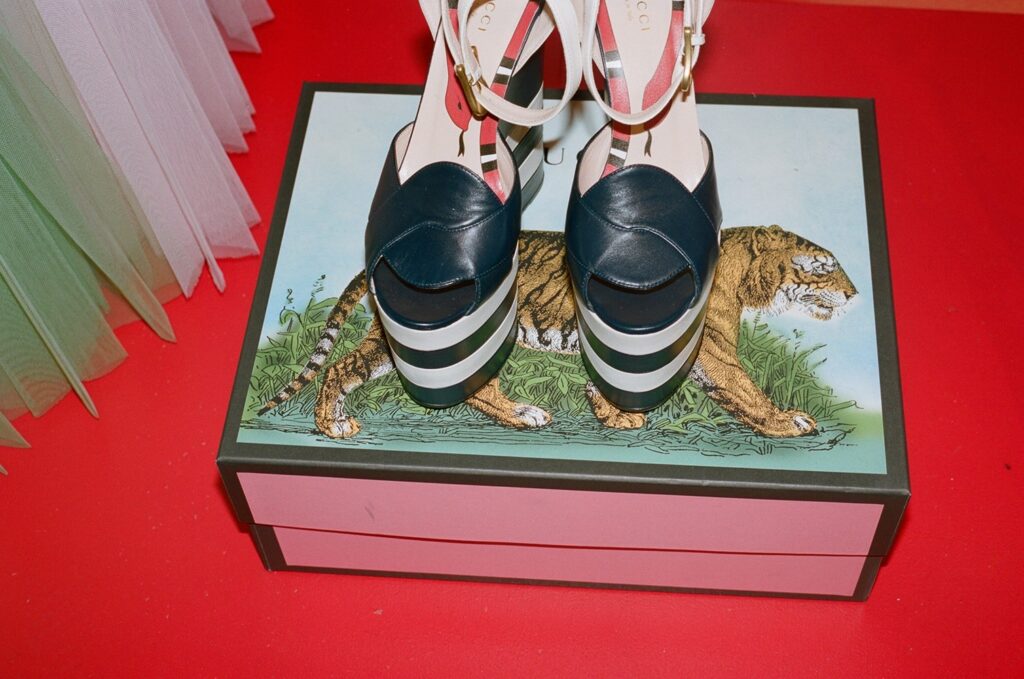

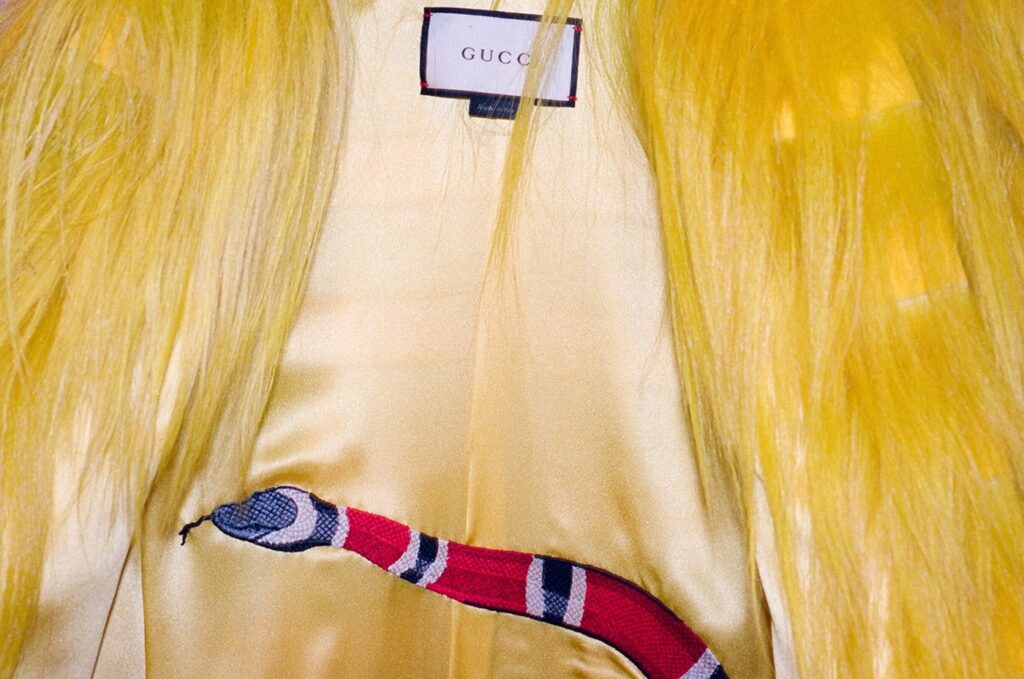

And yet like Bonello presenting Saint Laurent’s iconic 1971 collection, Michele’s “Rhizomatic Scores” collapses distances, bridging divides across place and history: baggy white trench coats give way to pink faux-fur jackets give way to sequin-studded cheongsams; the back of a piece might just as likely be emblazoned with embroidered parrots devouring corn snakes as a bedazzled AC/DC logo; the 1970s roll into the 1570s as Catherine de Medici meets, yes, Saint Laurent’s “Hommage aux Annees 40s.” Relationships are robbed of cause to give the director newfound freedom. Trying to pin down a start date for Michele’s collection becomes a futile effort as successive trends are chewed and regurgitated into the next retro wave; “a rhizome has no beginning or end,” of course, per Deleuze and Guattari. “It is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo.” Ulrich Lehmann borrows the phrase tigersprung from Walter Benjamin to describe fashion’s leaps back into time to drag the present ever forward. “If you take something that has no life with something that has life,” says Michele, “put together, it’s like a chemical effect.”

Bonello and Michele share a mission: to present us with images belonging to history without reducing them to it. Distances dissolve as each diachronic material crystallizes in its moment before the viewer, be it a fur-lined shoulder pad in Michele’s collection or Aymeline Valade as Saint Laurent’s muse Betty Catroux swaying in a narcotic nightclub. Both directors understand the key work of fashion, the direct phenomenological generation of ideas, feelings and sensations through the deepest possible engagement with surfaces.

I’ll resist here the obvious temptation to dissect the screen as a surface. Bonello ranks among our greatest living image makers — one need look no further than the luminous day-for-night photography in Zombi Child or the lush interiors of House of Tolerance — but more than simply composing images, Bonello composes in time. He structures Saint Laurent rhizomatically, beginning in a Paris hotel room in 1974 where Saint Laurent checks in under the name “M. Swann,” a Proustian reference which immediately calls to mind Deleuze on In Search of Lost Time:

…we are struck by the fact that all the parts are produced as asymmetrical sections, paths that suddenly come to an end, hermetically sealed boxes, noncommunicating vessels, watertight compartments, in which there are gaps even between things that are contiguous, gaps that are affirmations, pieces of a puzzle belonging not to any one puzzle but to many, pieces assembled by forcing them into a certain place where they may or may not belong, their unmatched edges violently forced out of shape, forcibly made to fit together, to interlock, with a number of pieces always left over.

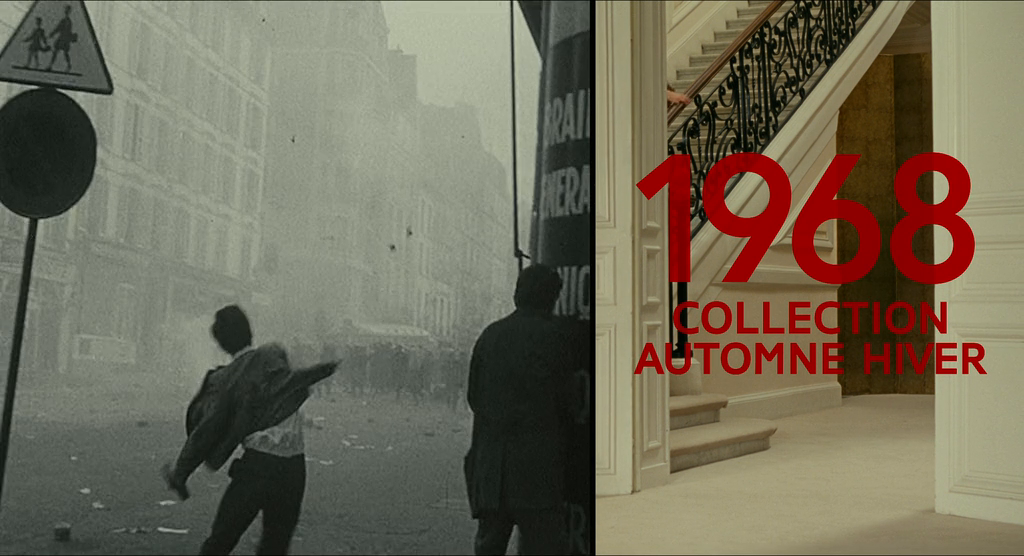

Scenes in Saint Laurent play out almost haphazardly, meandering through extended episodes one moment before abruptly cutting across years the next. Like Michele’s collection for Gucci, the leaps through time divorced from causal relations might feel disorienting or worse, tacky, in Bonello’s case calling to mind slews of lesser biopics condensing extraordinary lives into dull montages. And yet Bonello and regular collaborator Fabrice Rouaud’s cutting creates an eccentric rhythm. “But in a way it could be, again, a piece of memory. And after you have to cut again, like a collage. If you cut, it’s different. The way you combine together, it’s different.” It could be Bonello or Rouaud explaining the almost-glib split-screen montage placing YSL collections side-by-side against the events of ‘68, or it could be Deleuze unfolding Proust’s reminiscences — but it’s Michele again, offering what might be a summary of his project, or Bonello’s, or Saint Laurent’s or Proust’s:

“Your memory is not my memory.”

Now someone CashApp me a couple million or so to tell the story of the early days of Margiela…

Gucci A/W 2016 photos by Polly Brown

Leave a Reply