Maybe it was secretly a blessing that night when you couldn’t see the Big Dipper.

I’ve told this story before. When we first set up our best friends, we thought we had found the perfect match. After years of half-secret crushes, missed connections and ill-timed rendezvous (sound familiar?), the timing was finally right.

And a month later it was over. Their perfect match withered and was gone in only four weeks, another couple lost to the course of history.

I first met my best friend in our freshman year of high school, when he sold me a Squier P-Bass from the back row of our homeroom history class. In the twilight of our twenties, through the haze of desert dust and barroom brawls, he remains my closest brother, at least with whom I share no parentage. (Though he has taken to calling Carol “Grandma.”) Close from the very start, our early friendship puts me in mind of Balzac’s with his titular classmate in Louis Lambert:

It was long before I fully knew the poetry and the wealth of ideas that lay hidden in my companion’s heart and brain. It was not till I was thirty years of age, till my experience was matured and condensed, till the flash of an intense illumination had thrown a fresh light upon it, that I was capable of understanding all the bearings of the phenomena which I witnessed at that early time. …So it was time alone that initiated me into the meaning of the events and facts that were crowded into that obscure life…

In Plato’s Lysis, Socrates’ interlocutors ask him to define philos, whose varied meanings range from “friendly” to “beloved.” Socrates in turn asks his questioners whether desire for the object of one’s heart — be it the desire to love or the desire to befriend — can ever be separated from longing, from the space created in the subject who desires. We find Socrates punning on the multiple connotations of oikeios, which could include “like myself” or “belong to myself”:

…Τοῦ οἰκɛίου δή, ὡς ἔοικɛν, ὅ τɛ ἔρως καὶ ἡ φιλία καὶ ἡ ἐπιθυμία τυγχάνɛι οὖσα, ὠς φαίνɛται, ὦ Μɛνέξɛνέ τɛ καὶ Λύσι.—Συνɛϕάτην.—Ὑμɛῖς ἄρα ɛἰ φίλοι ἐστὸν ἀλλήλοις, φύσɛι πῃ οἰκɛῖοί ἐσθ’ ὑμῖν αὐτοῖς.

…Desire and love and longing are directed at that which is akin to oneself [tou oikeiou], it seems. So if you two are loving friends [philoi] of one another then in some natural way you belong to one another [oikeioi esth’].

It’s typical Socrates would drift between meanings, cherrypicking the one which best fits his thesis at any given moment, as if it were the same thing to recognize in someone else a kindred soul and to claim that soul as your own possession, as if it were perfectly acceptable in matters of the heart to blur the borders between yourself and the one you love. After all, the lover’s reasoning and hopes of happiness are wholly built upon this misapprehension, this blurred distinction. So the lover’s thought process moves continuously, scavenging the borderland of language, the domain of the vague where misunderstanding occurs. But for what does the lover’s heart scavenge?

In addressing his two philoi, Socrates intentionally confuses reflexive and reciprocal pronouns. When he says to them you belong to one another he uses as “one another” the word hautois, which more commonly means yourselves.

You belong to one another. You belong to yourselves.

Together with his “chum,” the precocious Louis Lambert, Balzac discovers the same truth:

Lambert himself explained everything by his theory of the angels. To him pure love — love as we dream of it in youth — was the coalescence of two angelic natures. Nothing could exceed the fervency with which he longed to meet a woman angel. And who better than he could inspire or feel love? If anything could give an impression of an exquisite nature, was it not the amiability and kindliness that marked his feelings, his words, his actions, his slightest gestures, the conjugal regard that united us as boys, and that we expressed when we called ourselves chums? …There was no distinction for us between my ideas and his. We imitated each other’s handwriting, so that one might write the tasks of both...

So if you two are philoi, Socrates tells the “chums,” then in some natural way you belong to one another. There is no distinction between one’s ideas and those of the other. Through his diction, Socrates plays upon the desires of the young lovers before him, dancing on the edge between words to offer the possibility of grasping a better truth, a truer meaning, than could be available from the separate senses of distinct words. But the glimpse of that enhanced meaning, when it flashes past, is a painful thing, inseparable from your conviction of its impossibility:

Words have edges. So do you.

But lessons in love are hard to take. Let us look to Virginia Woolf’s Neville in The Waves when he sees his beloved Bernard:

Something now leaves me; something goes from me to meet that figure who is coming, and assures me that I know him before I see who it is. How curiously one is changed by the addition, even at a distance, of a friend. How useful an office one’s friends perform when they recall us. Yet how painful to be recalled, to be mitigated, to have one’s self adulterated, mixed up, become part of another. As he approaches I become not myself but Neville mixed with somebody — with whom? — with Bernard? Yes, it is Bernard, and it is to Bernard that I shall put the question, Who am I?

I can’t speak to your feelings when we first met. But what both Socrates and Woolf offer here is the outline of what any lover, of anyone, learns in an instant from the experience of love: a vivid and terrible lesson on the nature of our own being. When desire inhabits the lover, there appears within him a sudden vision of a different self, perhaps a better self, compounded of his own being and that of his beloved as the self expands to include another in a complex, even unnerving occurrence sparked by erotic accident.

Remember Socrates: you belong to yourselves.

For three years, the French poet Paul Eluard, his Russian wife Gala and the German artist Max Ernst carried on a passionate three-person love affair, beginning in Cologne before moving to Paris and finally ending in Saigon. After the end of the relationship, none of the three would speak of it publicly, but by all accounts, it had been tumultuous, by turns stormy and fruitful, producing several important collaborations between Paul and Max.

By March of 1924 the situation had grown so tense that one night at a restaurant in Paris, Eluard simply stood up from his table and walked out.

Though André Breton wouldn’t publish the Surrealist Manifesto uniting his artistic impulses with those of Ernst and Eluard until October of that year, in 1922 he had already written a short piece titled Lâchez Tout, or Drop Everything.

| Lâchez tout. | Drop everything. |

| […] | |

| Lâchez votre femme, lâchez votre maîtresse. | Drop your wife, drop your girlfriend. |

| Lâchez vos espérances et vos craintes. | Drop your hopes and fears. |

| Semez vos enfants au coin d’un bois. | Leave your children in a corner of the woods. |

| Lâchez la proie pour l’ombre. | Drop the substance for the shadow. |

| Lâchez au besoin une vie aisée, ce qu’on vous donne pour une situation d’avenir. | Drop your easy life and preparation for a comfortable future. |

| Partez sur les routes. | Take to the road. |

“To be successful is to disappear,” Eluard once wrote, channeling his hero Rimbaud. Perhaps these were the impulses which led him to flee Paris. His yearning for an escape led him across the globe by boat, eventually ending in Saigon, where a few months later he invited Gala and Ernst to join him. Asked about his journey back in Paris, Paul would later dismiss it as un voyage idiot, a stupid trip. The Saigon affair and the long steamship journey to its end were never mentioned publicly by Ernst or the Eluards, and in due time historians came to regard it as a blank page in their biographies.

This feels like a mistake. Two close friends, each an astute and acutely articulate artist, aware of their ardor for the same woman, traveled across the globe to new landscapes and returned unaffected? Two artists devoted to self-expression in poetry and paint came back to Paris from an extended, emotionally laborious voyage and subsequently produced work unlike anything they had made before their departure, and either historians or the artists themselves would have us believe the two events were unrelated.

Brushing things under the rug is only possible when there’s something to hide.

We know almost nothing about the events of the trio’s trip to Saigon, but the vessels on which Ernst and the Eluards left Paris speak volumes about their personalities and circumstances: Paul fled the city as a lone wolf aboard a ship which had been a lone wolf herself, in name and function. The SS Antinous began life in the German Imperial Navy as the SMS Wolf, earning a place in naval history before her surrender to France by the German government after World War I.

Max, meanwhile, left France in style, more specifically the style to which he was fast — too fast — becoming accustomed, courtesy of his lover’s husband’s family wealth. For Gala, involvement with the arts was a passage to luxury, and she drew on Paul’s family empire to ensure she and her lover Max should travel in style aboard the elegant French liner, the SS Paul Lecat. Ernst and Gala lived une grande semaine, a week of entertainment and romance on board their own ship without the presence Gala’s husband cooling their affair. Clara Malraux best described it in detailing her own passage to Saigon: “Between Europe and Asia stretched days of reverie, nostalgia, hope, weariness, of heat that was barely dissipated by the fans one had to turn every-which-way to work.”

When the Eluards returned to Paris without Max, it was aboard the comfortable if outdated Dutch ship the SS Goentoer, a slightly decrepit liner which maintained its appearances of luxury and opulence even as it was destined for the breaker’s yard. If the metaphor for the Eluards’ crumbling marriage seems almost too on the nose, consider Max’s passage home, aboard the battered steamer the SS Affon, another ship consigned to the scrapheap, cast aside along with Max, no longer of use to anyone.

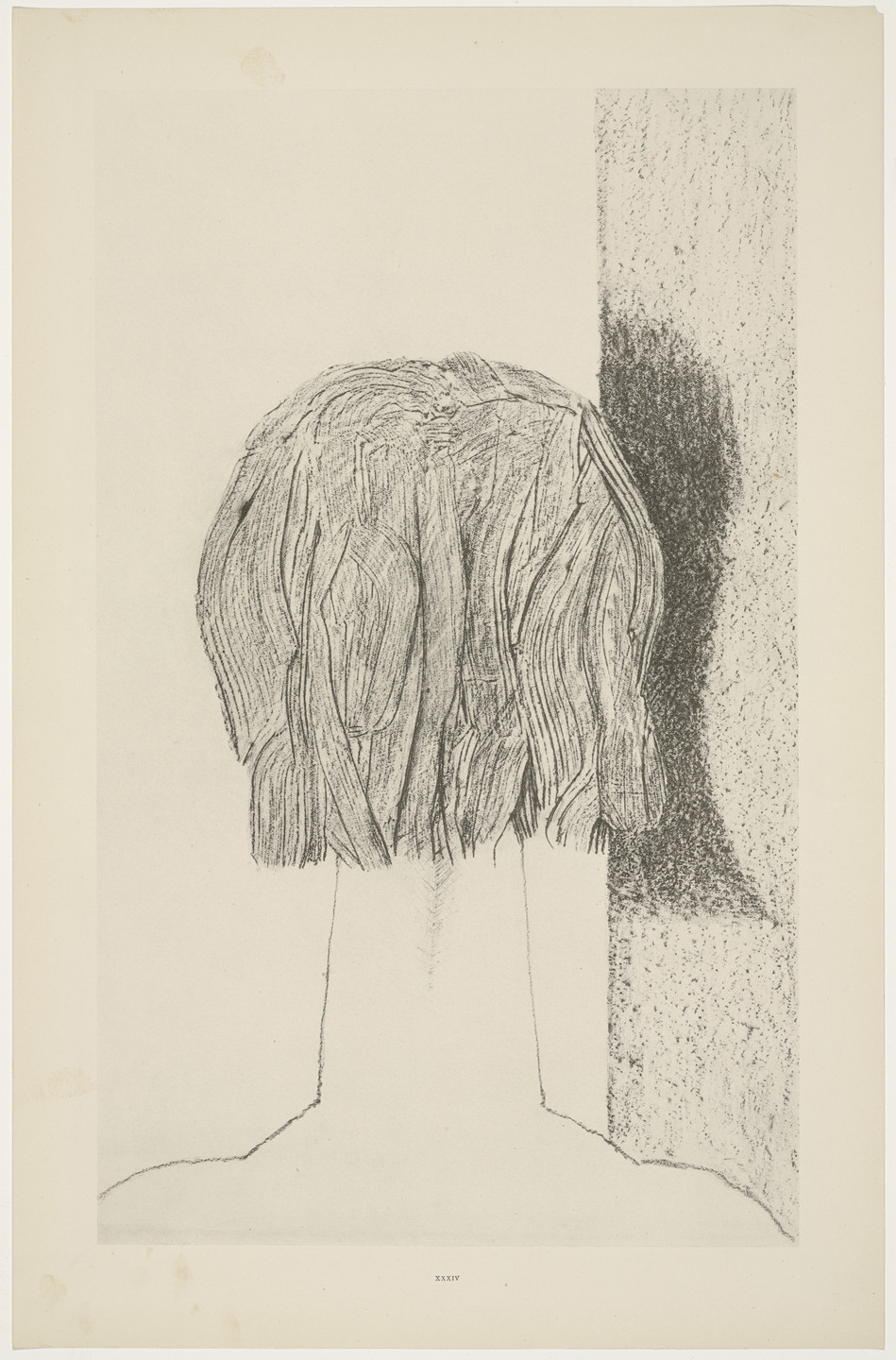

When Max returned to Paris alone, he began a massive series of paintings and sketches, about half of which would come to be published as a book titled Histoire Naturelle. The influence of his recent voyage by ship is obvious, as is his tormented emotional state: nearly all of the illustrations depict empty horizons broken only by a solitary island or mountain in the distance, as if the earth has been deserted of all human life. All human life, that is except one: a single illustration, the final one to appear in the book, depicts a woman with her back turned to the viewer, or to Max himself. Her name is Eve, la seule qui nous reste: Eve, the only one left.

The hundreds of portraits Max would paint of this same woman over the next decade confirm her dominion over his heart, and his most enduring work, Une semaine de bonté, pays tribute to la grande semaine Max and Gala shared aboard the SS Paul Lecat a full ten years prior.

Contrary to Max’s flurry of productivity which gave rise to Histoire Naturelle, Paul returned to Paris and began a process of diminution. In the year after the Saigon voyage, Paul published Au Defaut du Silence, a slim volume of fourteen single-line poems and four short pieces in verse and prose, accompanied by rattled illustrations Paul selected from nearly 130 scratched and shaky portraits Max sketched of Gala upon returning to Paris. The erratic nature of the drawings proves a perfect match for Paul’s minimal poems, such as the single line “A maquiller la démone elle pâlit,” which if it loses some of its abstract wonder when translated into English still seems to capture the heartache haunting both the poet and the painter: “Makeup blanches the she-devil.”

The other poems carry the theme of loss and frustration:

| Dans le plus sombres yeux se ferment les plus clairs | In the darkest eyes, the lightest close |

| Et se je suis à d’autres souviens toi | And if I belong to others, remember |

| La forme de tes yuex ne m’apprend pas à vivre | The shape of your eyes doesn’t teach me how to live |

| Elle m’aimait pour m’oublier, elle vivait pour mourir | She loved me to forget me, she lived to die |

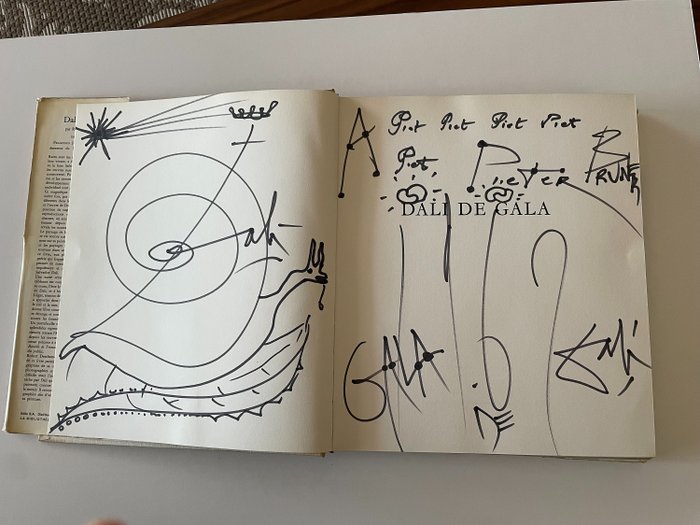

It probably comes as little surprise the Eluards’ marriage lasted only a few years after their return from Saigon before going the way of the SS Goentoer. Paul’s “she-Devil” would go on to marry Salvador Dalí, though she would still have multiple affairs with her ex-husband throughout their lives, even as Dalí began signing his paintings with both his and Gala’s names. “It is mostly with your blood, Gala,” he once told her, “that I paint my pictures.”

Remember Socrates: you belong to yourselves.

When she graduated early at age fifteen from the competitive Bronx High School of Science, Marilyn Hacker already took herself seriously as a writer. So it should come as no surprise she would fall in with another brightly burning young prodigy, her classmate Samuel R. Delany, who by twenty had already written ten novels. The two writers bonded over a mutual interest in other precocious genii, including Rimbaud and Natalia Crane, and when both were nineteen the couple drove to Detroit, the closest state which would grant their interracial marriage legal status. And so Hacker, a lesbian, married Delany, a gay man.

And yet despite this apparent incongruity, Hacker and Delany’s marriage was never a sham. Back in New York, the young couple welcomed a wide variety of guests into their home, from Hacker’s sometimes-mentor W. H. Auden — who nearly burned down the Lower East Side apartment flicking a cigarette into the garbage — to the men Delany picked up around town, immortalized both in his memoirs such as Times Square Red, Times Square Blue and in Hacker’s poems such as “Nights of 1962: The River Merchant’s Wife“:

He / was gone two days; might bring back, on the third, / some kind of night music I’d never heard: / Sonny the burglar, paunched with breakfast beers; / olive-skinned Simon, who made fake Vermeers…

Delany writes of his and Hacker’s early married life in The Motion of Light in Water:

Watching this thin young woman in thick glasses write her early poems, being around her while the detritus of daily life was transmuted into lines of dizzying musicality, not to mention being the poems’ first reader, was unspeakably exciting. It made my whole adolescence and early manhood an adventure — an adventure I was thrilled and pleased to be sitting at the edge of.

The perceptions apprehended in love appear somehow uniquely true, and more truly your own, as if they have been won from reality at personal cost. Perhaps they have been. The deepest, truest certainty is the conviction of your beloved as a necessary complement to yourself. From the depths of eros your mind conspires to create this vision, calling up possibilities outside reality. A new hybrid creature begins to rise, one you convince yourself is the true you despite the fact it is built from your and your lover’s dual natures. In Plato’s Symposium, Aristophanes offers his famous parable of the twin flames: long ago, humans were eight-limbed, two-headed creatures powerful enough to constantly threaten to overthrow the Gods. In response, Zeus cut all of the creatures in half, forcing each segment to spend their lives searching for their long-lost twin flames.

From the pit of desire, every lover feels they have found their other half. Suddenly possessed of godliness, for an instant the entire world feels within our grasp.

Then reality sets in.

I am not a god. I am not the hybrid creature. In fact, I am not even a whole self, sapped of my own nature as I have been by the forces of desire and lack. You find yourself convinced of the sinking suspicion Lacan was right all along: your newly-discovered knowledge of the possible is also a knowledge of what is lacking in the actual.

While on a tour of the province of Connacht, the ollave (a school of eighth-century Irish bard) Líadan of Corkaguiney happened to meet Cuirithir mac Doborchu, a fellow poet native to the region. Cuirithir begged Líadan to marry him, prophesying their progeny would be Ireland’s greatest poet. Weighing his proposal as she continued her travels, Líadan finally assented on one condition: a vow of chastity. The newlyweds would spend the rest of their lives in the monastery of Saint Cummine, where they avoided temptation by undertaking another agreement: for the rest of their lives Líadan and Cuirithir could choose to see each other without speaking or spend their lives separated by a wall, their only contact the words they could exchange through a gap between the stones. Poets at heart, they elected to spend their lives speaking invisibly.

Hacker and Delany’s daughter Iva was born in 1974, the same year the couple separated, though they would remain legally married until 1980. Two years later, Hacker would publish her aptly-titled second collection Separations, in which she included a poem titled “The Song of Líadan”:

(First, the word,

after the word, the cry,

after the cry, the song.

When will we know what we are seeking?)

You have imposed upon me a treaty of silence.

You have sealed my lips’ stone with passion.

You have melted the speaking stone with your hand’s heat

and your warm mouth is a band on mine.

There is a scream between us I have smothered.

There is a loud song frozen on the cold road.

A smothered scream, a loud song frozen on the cold road. Despite her vow of celibate speech, Líadan finds herself silenced:

My love is locked in a room without windows.

My ears are invaded by dissonant bells

sudden in cobbled silence. I cannot speak,

and in my body is a fear like metal.

In Líadan’s silence echo the mute words of another poet writing a millennium prior, Sappho. Her fragment 31 offers perhaps the definitive example of lovestruck silence:

| φαίνɛταί μοι κῆνος ἴσος θέοισιν | He seems to me equal to gods, that man, who |

| ἔμμɛν’ ὤνηρ, ὄττις ἐνάντιός τοι | ever he is, who takes his seat so close |

| ἰσδάνɛι καὶ πλάσιον ἆδυ φωνɛί— | across from you, and listens raptly to |

| σας ὐπακούɛι | your lilting voice |

| καὶ γɛλαίσας ἰμέροɛν, τό μ’ ἦ μὰν | and lovely laughter, which, as it wafts by, |

| καρδίαν ἐν στήθɛσιν ἐπτόαισɛν, | sets the heart in my ribcage fluttering; |

| ὠς γὰρ ἔς σ’ ἴδω ϐρόχɛ’ ὤς μɛ φώναι— | as soon as I glance at you a moment, I |

| σ’ οὐδ’ ἔν ἔτ’ ɛἴκɛι, | can’t say a thing, |

| ἀλλ’ ἄκαν μὲν γλῶσσα †ἔαγɛ λέπτον | and my tongue stiffens into silence, thin |

| δ’ αὔτικα χρῷ πῦρ ὐπαδɛδρόμηκɛν, | flames underneath my skin prickle and spark, |

| ὀππάτɛσσι δ’ οὐδ’ ἔν ὄρημμ’, ἐπιρρόμ— | a rush of blood booms in my ears, and then |

| βɛισι δ’ ἄκουαι, | my eyes go dark, |

| †έκαδɛ μ’ ἴδρως ψῦχρος κακχέɛται† τρόμος δὲ | and sweat pours coldly over me, and all |

| παῖσαν ἄγρɛι, χλωροτέρα δὲ ποίας | my body shakes, suddenly sallower |

| ἔμμι, τɛθνάκην δ’ ὀλίγω ’πιδɛύης | than summer grass, and death, I fear and feel, |

| φαίνομ᾿ †αι | is very near. |

At the beginning of Sappho’s poem we are nowhere, perhaps even locked in Líadan’s “room without windows.” The poem floats toward us from out of the darkness. We know not why the girl laughs nor what she feels about “that man, whoever he is.” That man cannot even be said to exist in the first line; he merely seems. In the line which follows he disappears into a pronoun (ottis) so ambiguous scholars have never agreed on its precise meaning. Google Translate will tell you it means simply “entity,” just as it will tell you the fourth line, σας ὐπακούɛι — according to Chris Childers, “your lilting voice,” and to Anne Carson “your sweet speaking” — translates to “he obeys you.”

In the next moment, the poet herself steps out from her hiding place behind a relative clause, when the combination of lilting voice and lovely laughter combine and “sets the heart in my ribcage fluttering” (Childers) and “puts the heart in my chest on wings” (Carson) “as soon as I glance at you a moment” (Childers), “then no speaking / is left in me” (Carson).

The poem cannot be said to center on characters per se — the girl referred to by the poet’s second person address is made only slightly more material than that man solely by her voice and laughter — but rather on the geometric relations inherent to their perceptions of each other and the distances between those perceptions. “That man… listens raptly” to you, to “your sweet speaking.” Maybe Google got it closer than we thought: He obeys you. The poet sees him, then “glance[s] at you a moment.” Their attentions converge on your lovely laughter, forming a triangle.

And yet for Sappho the triangle, constructed though it may be from unbridgeable gaps between perceptions, forms not the infrastructure of jealousy, despite what some critics have read in the fragment. In the fifteenth century Italian dramatic dances known as bassa danza, a dance called Jealousy featured three couples swapping partners and during which “each man goes through a stage of standing by himself apart from the others.” Instability preys on the mind of the jealous lover: it’s a dance in which everyone moves.

Sappho, on the other hand, cannot move. Death, I fear and feel, is very near; were she to partake in the bassa danza and change places with that man, the reader gets the sense she would be destroyed. “Standing by [her]self apart from the others,” Sappho fears not for her position, nor does she appear to envy that man his. Her attentions are directed purely and solely at you. Despite seeming “equal to the gods,” Sappho places that man as a mere observer, as if his position is only to measure and confirm the thin flames which prickle and spark. His rhetorical placement is not uncommon in love poetry: think of Pindar, who sees his love and “melt[s] like wax as the heat bites into it” while another “whose black heart was forged of adamant or iron in a cold flame” sits by unmoved, or the similar Hellenistic epigram which tells the reader “if you looked upon my beloved and were not broken by desire, you are totally god or totally stone.”

But while he seems to me equal to gods, that man, whoever he is is not totally god or totally stone. Again, these characters cannot be said to truly exist in any embodied form, and the clearest location the action of the poem finds is revealed only once Sappho’s own heart begins to flutter in her ribcage, shifting focus from that man and you to the inner workings of Sappho’s own heart and mind. Death, I fear and feel, is very near; Carson translates this final line as

dead — or almost

I seem to me.

“Equal to the gods,” he seems. “Dead — or almost,” Sappho herself seems.

Sappho’s fragment is a poem of seeming, of appearances and sensations as they appear within the mind. Hers is not a poem of the material world. Pindar situates himself contra his impassive rhetorical observer — only an iron-hearted god, one whose heart is beyond nature, could be unmoved by the object of his desire — and thereby aligns himself with normative human desire. That normative desire has as much a place in Sappho’s poem-world as jealousy. This is the record of how a singular mind constructs a singular desire. That man is no mere rhetorical device or expression of sentiment. He is an intention. Desire seems to Sappho — it takes real, physical shape — in the form of a three-point structure, what we might in modern parlance call a love triangle. Inside that triangle seems to Sappho the very constitution of desire: the lover, the beloved, and the gap between them. If desire is lack, it can only be activated by the space between the other two components. Lack bridges them even as it divides, keeping two from becoming one. That man... seems to me equal to gods, while Sappho fears and feels the close presence of death. Both responses live in the poet’s mind. No one moves in this dance; there is no need. Desire dances between them.

Remember Socrates: you belong to yourselves.

He / was gone two days; might bring back, on the third, / some kind of night music I’d never heard…

“Are you not amazed,” asks Longinus in De Sublimitate, “how at one instant she summons, as though they were all alien from herself and dispersed, soul, body, ears, tongue, eyes, color? Uniting contradictions, she is, at one and the same time, hot and cold, in her senses and out of her mind, for she is either terrified or at the point of death. The effect desired is that not one passion only should be seen in her, but a concourse of the passions. All such things occur in the case of lovers, but it is, as I said, the selection of the most striking of them and their combination into a single whole that has produced the singular excellence of the passage.”

Another, shorter fragment displays Sappho at perhaps her most powerfully concise:

οἶον τὸ γλυκύμαλον ἐρɛύθɛται ἄκρῳ ἐπ’ ὔσδῳ,

ἄκρον ἐπ’ ἀκροτάτῳ, λɛλάθοντο δὲ μαλοδρόπηɛς,

οὐ μὰν ἐκλɛλάθοντ’, ἀλλ’ οὐκ ἐδύναντ’ ἐπίκɛσθαι

…like the reddening apple,

at the tip of the topmost twig,

which the apple-pickers missed —

or no, not missed entirely;

the one they could not reach.

Fragmented; incomplete; perfect. One sentence, no verb, no subject. No arrival at its main clause. One simile, like the reddening apple, but what is like can never be known. The comparison vanishes, missed — or no, not missed entirely; the one they could not reach. Grasping hands reach, enclosing around empty air in the final line, for the apple dangling just a few lines above.

These brief lines (translated above by Gillian Spraggs) trace a trajectory from perception — the apple — to judgment — why it remains unpicked. After its first appearance, the poet adds detail, finding a precise location “at the tip of the topmost twig.” From location in space comes location of a different kind, as Sappho searches for an explanation — the apple-pickers missed. Then that logic is further extended: they could not reach. The fragment is one of constant amendment, each successively revealed element subjected to correction, impressions revised and reasserted. Sappho’s syntax echoes this process as initial interpretations extend from each other: akrō… akron… akrotatō lelathonto… eklelathont’.

(Again, Google Translate offers an evocative poetic fragment of its own from just those few syllables:

to the end / on screen / unheard, spoken / they cried)

Beyond diction, Sappho’s rhythm again marries content and form, as the bouncing triplets of the first lines stretch out into evenly-stressed spondees by the fragment’s end, fingers splayed, reaching for the apple. Even the computer translation above cannot help but echo Sappho’s meter, the dactyl to the end giving way to solemn disyllabic phrases as the apple looms further out of reach. “Desire isn’t appeased by its object, only irritated into something more than desire that can join with the stars to inform the chaotic heavens with sense,” writes Delany in his novel Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand. “Fingers can’t point to anything anymore. And without such indications — oh, I still walk where I walked, look where I looked, but where I saw what once seemed wonderful, I see so little now — I feel so little.”

Centuries removed from the Book of Genesis, we begin with an apple and find ourselves in unending longing. Eros’ perpetual reach is defined in action even as its attempt is perennially foiled. Between fingers closing around the unreachable, between glances stolen across crowded rooms, between I love yous and I love you, toos, the specter of desire is given space to haunt. Grasping reach, furtive looks, I love yous, all are mere echoes through space of the one incontrovertible, insoluble boundary between us: the border between flesh and self. Desire defies the edge, forcing together opposites. Eros bounds from the lover to the object of their affection and springs back into the heretofore unnoticed abyss within the lover. No poet truly writes of their beloved. A poem is always and can only ever be a description of a hole.

A pendulum strikes on metal

and in my quick heart is the silence of bound hands.

So says Hacker’s Líadan.

Remember Socrates: you belong to yourselves.

Here’s another story I’ve told before:

My mother-in-law contends she met her soulmate early in life. She had just returned to San Diego from an aborted move to Oregon with a friend from high school. One dream shattered, she embarked on another, and in the fall of 1970 she began the journey of putting herself through college.

Reading under a tree on campus one day, my future mother-in-law found herself interrupted by a dog charging after a ball and into her lap, or as she puts it, “This beautiful white dog came up on me, followed by this beautiful man.” A whirlwind romance with the beautiful man (whose name was Michael) followed, including years with the beautiful dog (whose name was Baggins). Convinced their meeting had been fate, Michael proposed in short order and the two were married. Only later would Michael admit he had thrown the ball intentionally so Baggins would charge into my mother-in-law’s lap. Sometimes we need to take fate in our own hands.

What followed were years spent reveling in storybook love even as circumstance led the couple to move first into a trailer in West Virginia and finally onto Michael’s family ranch in Texas. It was on the farm where tensions with Michael’s conservative family finally led the couple to separate.

My mother-in-law married two more times: once unhappily (perhaps unsurprisingly) to a jazz guitarist with whom she suffered multiple miscarriages, and once happily to a kind and gentle employee at her favorite bookstore who would finally give her a daughter and an entirely new life, one they share to this day.

My in-laws are happy together. I have never doubted the fulfillment they grant one another. And yet my mother-in-law maintains to this day Michael was her soulmate, The One, the man with whom she was meant to be. When I put myself in her position I can only feel what seems like a dire compromise, having built the life she wanted in a way she didn’t. Theirs has always struck me as the saddest possible ending to a love story, to know you’ve met your perfect other half only to lose them forever, not because of the permanence of a tragic death but because of the circumstance of a tragic life, like Líadan and Cuirithir sharing a monastery forever, separated by their wall.

The two kept in touch until Michael’s death, and somewhere there is a deeply heartbreaking photo of him holding her infant daughter. When I put myself in his position I can only feel what I imagine it would be like to watch someone else raise the child who should have been yours.

This next story gets a little confusing, crisscrossing as it does between many famous players. William Carlos Williams was in college when he met Annie Winifred Ellerman, better known by her pen name Bryher, after one of the British Scilly Isles. She was also the daughter of the secretive shipping mogul John Ellerman, at that time the richest Englishman who had ever lived and the owner of an enormous estate in Central London where Bryher grew up. (She hated it, deeming it a “stuffy mansion.”) Around this time, Williams also met the poets Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle, who at the behest of the former would soon start calling herself by the initials H.D.

H.D. had first met Ezra Pound even earlier, at a Halloween party in a Philadelphia suburb in 1901, when she was only fifteen. Pound was already a student at the University of Pennsylvania, as was Williams. They got to know each other better beginning in 1905 when H.D. began at the women’s liberal arts college Bryn Mawr. In those days Williams called H.D. “a bizarre beauty,” a description which may have fit Pound as well:

I don’t recall my first meeting with him. Someone had told me there was a poet in the class. But I remember exactly how he looked. No beard, of course, then. He had a beautiful heavy head of blonde hair of which he was tremendously proud. Leonine. It was really very beautiful hair, wavy. And he had his head held high. I wasn’t impressed but I imagine the ladies were.

Williams may have been in love with H.D. himself, but she was attracted to Ezra and they became engaged.

Ezra was the official lover, but Hilda was very coy and invited us both to come and see her. Ezra said to me, “are you trying to cut me out?” I said, “no, I’m not thinking of any woman right now, but I like Hilda very much.” Ezra Pound and I were not rivals, either for the girl or for the poetry. We were pals, both writing independently and respecting each other.

H.D. wrote to Williams in 1905 that she was going to dedicate herself to “one who has been, beyond all others, torn and lonely — and ready to crucify himself yet more for the sake of helping all — I mean that I have promised to marry Ezra.” Williams got the consolation prize of being a best friend: “you are to me, Billy, nearer and dearer than many — than most.”

H.D. invited Ezra and his parents to Sunday lunch at her very conservative parents’ house. Her father, director of the University’s Astronomical Observatory, disapproved of Ezra from the start. H.D.’s cousin recalled Ezra’s debut appearance; he came with no hat over his wild mass of hair, wearing tortoiseshell glasses. And “while ties were the absolute standard of dress for men, he wore none, but had his shirt open at the neck in true Byronic fashion… After the meal he read his poems to his adoring parents and Hilda, while the rest of us listened in confused wonderment.”

The engagement was soon over. H.D. wrote to Williams that Ezra had met someone else, but that she was “happy now as I was before – and I know that God is good.”

Just over a decade later H.D. would publish her first collection of poems, Sea Garden, opening with the poem “Sea Rose:”

Rose, harsh rose,

marred and with stint of petals,

meagre flower, thin,

sparse of leaf,more precious

than a wet rose

single on a stem—

you are caught in the drift.Stunted, with small leaf,

you are flung on the sand,

you are lifted

in the crisp sand

that drives in the wind.Can the spice-rose

drip such acrid fragrance

hardened in a leaf?

Williams’ old college friend Bryher read H.D.’s poems and committed each one to memory. On July 17, 1918 Bryher found her poetic idol with “the sea in her eyes” when she opened the door of her Cornwall cottage and said “in a voice all wind and gull notes, I have been waiting for you.” H.D. asked Bryher if she had seen the puffins in the Scilly Isles off the coast of Cornwall; Bryher asked H.D. if she would go there with her.

Bryher came at the right time: H.D. was poverty-stricken, abandoned by both her husband, Richard Aldington, and her lover, Frances Gregg. And she was pregnant, possibly with D.H. Lawrence’s child. (Nobody knows concretely if H.D. had a physical affair with D.H. Lawrence; they both burned all their letters to each other.)

Bryher brought H.D. to the Scilly Isles to nurse her through the pregnancy, this time resulting on December 13, 1919, in a daughter named Perdita – the Lost One – who the two women brought up together. Ezra Pound visited the hospital the day before Perdita was born, carrying an ebony stick with which he pounded the floor, declaring his happiness for the couple. His only problem, he said, was that the child wasn’t his.

Soon after Perdita was born, Bryher married Robert McAlmon, a penniless writer supporting himself by modeling nude for art classes. If at first glance the marriage comes as a surprise, all was not what it seemed. Bryher and McAlmon had first met when H.D. contacted her old college friend William Carlos Williams to say she and a friend would be visiting New York; would he like to drop round their hotel for tea? At the time Williams was working with McAlmon on Contact magazine; he asked Robert if he would like to come along.

Bryher turned out to be a very good thing financially, not only for McAlmon, but for many of his friends. Sylvia Beach, owner of the legendary Paris bookshop Shakespeare and Company, regularly wrote to both Bryher and H.D., to whom she spoke as to a friend. Conversely, Beach wrote to Bryher in gratitude, as to a patron. In several letters Sylvia thanks Bryher for saving her from financial ruin. Years later Beach would write to Bryher on her fiftieth birthday, “It was in one of the earliest days of ‘Shakespeare and Company’ that you came into my bookshop and my life, dear Bryher, and that we became a Protectorate of yours. We might have had the words: ‘By Special Appointment to Bryher’ painted above the door.”

When they first met, McAlmon didn’t know – or at least claimed not to – of Bryher’s family wealth. He knew she wasn’t just another poor poet, though. “Her family name meant little to me,” he declared. “However, I knew she was connected with great wealth.” At least that was the story McAlmon, Williams, and others in their circle told. Morley Callaghan, a reporter colleague of both McAlmon and Hemingway, believed it, or at least he didn’t believe in looking a gift horse in the mouth; after the divorce McAlmon was left quite wealthy, earning him the nickname McAlimony.

“It had been a very nice thing for him to marry a rich girl and get a handsome divorce settlement, but I had always believed his story that he hadn’t been aware it was to be a marriage in name only; he had insisted he was willing to be interested in women. And with the money, what did he do? Spend it all on himself? No, he became a publisher, he spent the money on other people he believed in.”

But McAlmon certainly wasn’t telling the whole truth. In her edited version of McAlmon’s Being Geniuses Together, Kay Boyle prints a letter he wrote Williams:

“Then you’d better know this, Bill. I didn’t tell you in New York because I thought it wasn’t mine to tell. But Bryher doesn’t mind… The marriage is legal only, unromantic, and strictly an agreement. Bryher could not travel, and be away from home, unmarried. It was difficult being in Greece and other wild places without a man. She thought I understood her mind, as I do somewhat and faced me with the proposition. Some other things I shan’t mention I knew without realising. Well, you see I took on the proposition.”

It was a good proposition, for both parties: McAlmon received access to money and a trip to Europe where he could meet his literary heroes like James Joyce. Bryher got both a publisher and a beard to cover her relationship with H.D., even if he wasn’t exactly the kind of husband her parents might have wanted — a penniless writer taking his clothes off for a living — but still in their eyes and those of the public probably preferable to a lesbian lover. This was conservative London, not cosmopolitan, liberated Paris.

Bryher and McAlmon were married in New York on Valentine’s Day, 1921. They set off for Europe immediately, paid for by Bryher’s father Sir John Ellerman. H.D went with them.

In Bid Me to Live, H.D. wrote about the “precarious nature of flying in the face of convention” as “a very, very thin line to toe, a very, very frail wire to do a tight-rope act on.” This tightrope act was one both Bryher and H.D. had to learn to walk. The darker elements of their relationship coexisted with rich pleasures and discoveries. They suffered and thrived in the modernist moment of looking forward and backward, adventuring, hiding; inventing styles of disclosure, breakage and continuity. Bryher and H.D.’s refashioned family involved years of travel, cover, and marriages of convenience complicated by stigmas against female sexuality. The pair’s nostalgic Hellenism, their unified desire to re-enter the Greek past was a means for both survival as “queers” in lived time and for transcending the borders of space and time. Remote in the Scilly Isles, they found a refuge.

Remember Socrates: you belong to yourselves.

After Perdita’s birth, H.D. began writing Paint It Today in 1919, which she left unfinished, abandoning the text two years later. In the manuscript, she took wavering steps towards a relationship with her first lesbian lover Frances Gregg, steps she would never forget or erase. She had tried a lesbian romance and it had short-circuited; she had tried a traditional marriage and it had ended in betrayal and pain. She had been more romantically attached to Gregg than to Pound or Aldington, as Paint It Today expressed, but by its conclusion, all her loves were subsumed by Bryher’s and the arrival of the baby. The text H.D. did manage to finish while recovering in the Scillies, Notes on Thought and Vision, reads like a love poem to Bryher.For her part, Bryher composed love songs that would make up 1922’s Arrow Music, including “Eros at Sea,” which emerged out of the Scilly setting, complemented by H.D.’s lessons on Greek myths. Bryher’s poems are interlocking parts of a dialogue with H.D., who in turn began writing interpretive translations of Sappho fragments which would later appear in both the collections Hymen and then Heliodora in 1924.

This probably all sounds more complicated than it needs to be, but is meant to display the pair’s almost overwhelming productivity during this period, nearly matching Max Ernst’s upon his return to Paris from Saigon. Considering how exhausted both women were after Perdita’s birth, their creative output during this “vacation” was noteworthy. Much of what they wrote existed as a dialogue between them. The pair likely consummated their affair only after Perdita was born, most likely at Mullion Cove in Cornwall, whose private cliffs and wilderness gave H.D. a chance to educate her “dear girl” in the sensuousness she understood; they would also become collaborators in what we might call, for lack of a better phrase, a folie à deux: a shared hallucination, specifically an experience of “drowning” or merging with the other. Bryher assessed the situation in a poem: “This was the end of hope — to wait for the sea, to drown, not to re-enter the desolation she had left.” The poem, both personal and formal, fulfilled the Hellenic incantation to a beloved.

Bryher’s “Eros at Sea,” inspired by Keats’ “Hyperion,” features a “female supplicant invoke the god Eros, who rises from the sea like his mother Aphrodite,” who is often a figure for H.D. within Bryher’s writing. Given H.D. had just given birth, envisioning her as Aphrodite would have been apropos. When the Gods speak and ask the unnamed supplicant her desire, we get the evocative passage: “Words died. All her body spoke its longing but her lips could not utter her request… This was the end of hope — to wait for the sea, to drown, not to re-enter the desolation she had left. How could she, having looked on Beauty, live?” To be in love was devastating, as H.D. herself writes in her poem “Eros,” borrowing from Sappho:

to sing love

love must first shatter us.

Bryher and H.D. experienced intense ups and downs, strains, exhilaration, anguish. They were in love.

In 1965 Samuel Delany took a sort of sabbatical from his marriage, hitchhiking to the Gulf Coast to spend a summer on shrimp boats before spending a year in the Mediterranean, eventually returning to the U.S. to live on communes in New York and San Francisco, an experience he details in his excellent memoir Heavenly Breakfast. “Chip is interested in the labyrinth,” says Junot Díaz, referring to Delany by his well-known nickname. “He’s interested in how the only path to any kind of understanding is to get lost.”

The coming of spring is insidious and cruel.

The mist pervades my throat as it melted the crystal

my voice was. I am weak, and I much preferred

the hard agreement of our truce of gauntlets.

Now, let’s finally get back to that first story we started.

Some weeks after their breakup, my best friend and I convened for a night of playing music and ingesting foreign fungi, a confluence of events which unsurprisingly created the conditions for a relationship postmortem.

“I should text her,” he offered to no one in particular. “I should reach out and see how she’s doing.”

I told him that unless he hoped to rekindle their relationship, reaching out didn’t strike me as the best idea. He made it clear he still cared for her deeply. Why then, I asked, did they have to break up?

“I just need my freedom,” he said. “To do all this.” He gestured around the dirty garage at our other friends, at the assorted battered instruments.

I reminded him I had been married nearly five years already by that time, as if to say I’m still here. I’m still doing this. I reminded him of my time on the road, of my travels around the world playing music, pursuing one thing I love while separated by half the globe from the other. I didn’t say it then, but Díaz’ comment about Delany flashed across my mind: The only path to any kind of understanding is to get lost.

One night on tour with Executioner’s Mask in Florida, the distance very nearly became too much. After the protracted breakup of my band of a decade-plus, after two years shuttered inside as the pandemic festered, the very idea of spending a night in Orlando in a room full of strangers felt suffocating and beyond alien. Outside the bar, I called home in near-hysterics, ready to book a flight back to California. I don’t remember the exact words that assured me everything would be okay, but I know they fell somewhere along these lines: The only path to any kind of understanding is to get lost.

Back in that garage my best friend and I kept swallowing mushrooms and playing shitty Neil Young covers. If most people know the lyrics to the song “My My, Hey Hey,” it’s for the line Kurt Cobain quoted in his suicide note:

It’s better to

burn out

than to

fade

away

John Lennon famously tried taking Neil Young to task over that line in a Playboy interview.

I hate it. It’s better to fade away like an old soldier than to burn out. If he was talking about burning out like Sid Vicious, forget it. I don’t appreciate the worship of dead Sid Vicious or of dead James Dean or dead John Wayne. It’s the same thing. Making Sid Vicious a hero, Jim Morrison — it’s garbage to me. …What do they teach you? Nothing. Death. Sid Vicious died for what? So that we might rock? I mean, it’s garbage you know. If Neil Young admires that sentiment so much, why doesn’t he do it? Because he sure as hell faded away and came back many times, like all of us. No, thank you. I’ll take the living and the healthy.

To which Neil Young responded:

The rock ‘n’ roll spirit is not survival. Of course the people who play rock ‘n’ roll should survive. But the essence of the rock ‘n’ roll spirit to me, is that it’s better to burn out really bright than to sort of decay off into infinity. Even though if you look at it in a mature way, you’ll think, “well, yes… you should decay off into infinity, and keep going along.” Rock ‘n’ roll doesn’t look that far ahead. Rock ‘n’ roll is right now. What’s happening right this second. Is it bright? Or is it dim because it’s waiting for tomorrow — that’s what people want to know. And that’s why I say that.

In their baby boomer rockstar daze, Lennon and Young here seem almost to unwittingly echo H.D.’s plea to Bryher at the dawn of the century:

to say,

to speak one word of the joy we had

(to people who anyway don’t want to understand)O don’t you, don’t you understand, you must count yourself now, now among the dead?

This spirit is not survival.

Historians can’t agree on who, but someone — maybe Archilochus — captured perfectly the sensation of being bound, even gagged by desire:

τοῖος γὰρ φιλόπητος ἔρως ὑπὸ καρδίην ἐλυσθɛὶς

πολλὴν κατ’ ἀχλὺν ὀμμάτων ἔχɛυɛν,

κλέψας ἐκ στηθέων ἁπαλὰς ϕρένας.

Such a longing for love, coiling up under my heart,

poured much mist over my eyes,

stealing out of my chest the soft lungs.

The poem opens with τοῖος, a demonstrative pronoun meaning “such,” corresponding to οἷος, “as.” The first line establishes the expectation of an answer which never arrives. The grammatical economy is flawless, down to the perfect positioning of eros coiled in the very center of the line. Six round o vowels and four pairs of clustered consonants build tension through the line as eros rolls itself up in the poet’s heart. When we reach the speaker’s heart, he borrows a participle, ἐλυσθɛὶς, from Homer: coiled in a ball at the feet of Achilles is how Priam offers the body of his son in supplication at the end of the Iliad, and Odysseus escapes the Cyclops coiled in a ball under the belly of a ram. Like Priam and Odysseus, desire’s power lies hidden under a posture of vulnerability, and like Homer, Archilochus sets the participle at the end of the line, quietly casting a shadow of menace over the preceding words.

In the second line, mist rolls down in four nasal consonant streams, -lēn, -lun, -tōn, and -en, another Homeric allusion to the “mist before Achilles’ eyes,” darkening men’s vision in the moments preceding death.

And with the poem’s third line, death takes its toll; lungs torn away, speech impossible, the poem must end. Five serpentine sibilants chase the thief desire, but the poem cuts off before it can complete its meter. What survives of the poem, like Sappho’s, is only fragmentary, and yet its broken nature perfectly captures the effect of desire, stealing the lover’s lungs, cutting off τοῖος as it grasps for οἷος.

H.D. again:

it was beyond any words;

there were no words

even in our glorious speech

that could hint the joy we had then;

how can we to-day in a crude tongue,

in a strange land hope to say

one word that can hint at the joy we had

when the rocks broke like sand under our heels

| Desire gnaws in her slender breast and pain eats out her heart | writes Sappho. |

| You have snatched the lungs out of my chest and pierced me right through the bones | accuses Archilochus. |

| You have worn me down | (Alkman 1.77 PMG), |

| grated me away | (Aristophanes’ Assemblywomen…), |

| devoured my flesh | (…and Ranae.), |

| sucked my blood | (Theocritus), |

| mowed off my genitals | (Archilochus again), |

| stolen my reasoning mind | (Theognis of Megara). |

Desire, the butcher, tears away limbs, eviscerating lovers. The lovers resemble Aristophanes’ fabled race of dual-natured humans, ripped in half by Zeus. Hacker’s Líadan continues:

As the pulled root shrieks, as

the struck stone breaks, as

glass at a note-thrust

cracks, as

ice slivers from the sudden shard of spring;

cracked, broken, and slivered, shrieking

under the mad, sharp stars,

I shall dance, beloved,

and sing passion’s reason to the blind walls.

That night, my best friend asked me for the secret. How do you maintain a love across obstacles, distance, years?

I can’t guarantee I remember the exact words I told him that night, and given the saprodelic circumstances I won’t promise that whatever I said rang with the eloquence of Líadan or Hacker. But it’s those two poets whose words ring in my mind now when I think back on that night.

How do you do it? he asked.

No matter where on this planet our cracked, broken and slivered paths wend, I know you and I will always look up, dancing, beloved, and singing passion’s reason under the same mad, sharp stars.

So maybe it was a blessing that night when you couldn’t see the Big Dipper. Maybe we can’t even share the same stars. Maybe space in its infinite expansiveness can’t give me enough room to run away from how I feel about you.

As I write this I can’t help but look at the notes you’ve written me which I keep arranged at my desk.

These last few weeks have been stolen from me.

I cannot focus on anything.

Every thought eventually leads back to you and blurred vision of us tangled up.

I can still feel every mark you ever left.

We joke often about the ability of one of us to speak the other’s thoughts before we ourselves can verbalize our own feelings. I think again of Balzac and Louis Lambert: There was no distinction for us between my ideas and his. My handwriting is no match for yours, which makes it all the sweeter to look up to the paper you tore from your notebook and read my thoughts in your pen:

I think I have never met anyone like you and I surely know I never will again.

The pain is gut wrenching because you will never truly be mine.

But some force unknown to me has given you to me for a time.

Selfishly I pray I can keep you here longer.

Or the postcard from Montana:

You are my angel and my dream come true. Thank you for being exactly who you are. Thank you for showing me what it means to love + be loved. You know you have my whole heart always.

“You show me colors I can’t see with anyone else.”

I know you’re always going to be The One for me. It’s when I have to qualify the statement with “That Got Away” that my heart breaks anew.

I don’t know if I can be your friend. To see you as anything but my partner, the true Love of My Life, feels like torture. But I hope you can take this statement to heart: whenever you need anything in life, I will be there. I will be loyal to you for the rest of my life, and if ever a situation arises wherein I could be of service to you, I promise you can lean on me.

I won’t leave any room in this book for you to write.

I won’t leave any room in my heart for anyone else to live.

But both will always belong to you, to keep or toss aside as you see fit.

Who knows, if you never showed up, what could have been? I had a marvelous time ruining everything.

I will always love you, huckleberry.

Leave a Reply