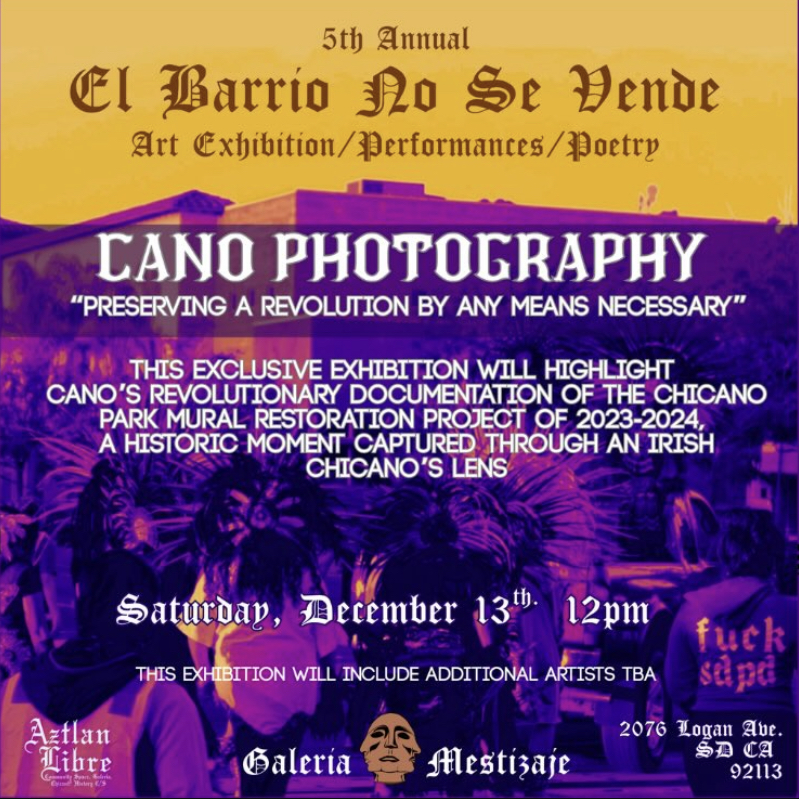

Coinciding with Tall Can’s recent release from prison, Aztlan Libre’s fifth annual El Barrio No Se Vende show offered the perfect opportunity to showcase his photography documenting the restoration of the Chicano Park murals.

The theme for the show was “Preserving a Revolution By Any Means Necessary,” and the statement Aztlan Libre and Galeria Mestizaje released before the show spells out its aim clearly:

Artists have a responsibility to use their art as a tool to show the injustices our raza face daily! Art historically has been used to educate and to call out injustices our people face. El Barrio No Se Vende is a reminder of an artist’s responsibility to create for their raza!

This year our carnal Jesse “Tall Can” Cannon will be showcasing his photography that was taken during the historic Chicano Park Mural Restoration Project of 2023-2024. During this time we were able to successfully employ hundreds of people from the community and I knew we needed Jesse behind the lends to document this historic moment.

This was a revolutionary point in time as we were able to take state funds that normally would go to another entity and put them directly into the hands of the community. We hired formerly incarcerated, houselss, residents, activists, and other Chicano Park supporters to help clean and restore our piece of Aztlan!

Of course this was not an easy effort. When we were at our highest point of unity we faced attacks from police, nonprofits, provocateurs, ad even our won raza! This unfortunately led to a lot of our brothers and sisters who were helping on the project to be arrested periodically throughout its duration.

The system could not believe our raza was actually working to beautify their varrio.

Brother Tall Can unfortunately was one of the ones the state had their eyes on due to his history of defending our most vulnerable communities and he ended up serving close to 2 years as a political prisoner. Now that he is free it is time to celebrate his work.

In my post when we dropped pilostyles wildflower I alluded to the challenge facing contemporary art resulting from its two contradictory, overlapping goals: the self-sufficient autonomy of art and its pretension to social impact.

On the level of the rhetoric of resistance and critical discourse, socially engaged art within the institutional paradigm of galleries and universities claims emancipatory, democratic sociality. But when it came to validating artistic achievement, the counter-aesthetic aspects of socially engaged art are evaluated not by their sociopolitical impact but by the extent of the art’s own institutional self-negation.

Take for example Artur Żmijewski and Joanna Warsza’s curation of the 7th Berlin Biennale in 2012, which rejected the exhibition format for a political occupation of art institutions, including the transplanting of 320 trees from Auschwitz to Berlin, an invitation to members of the Occupy movement to take over the Kunst-Werke Institute, and a forum organized by Jonas Staal for the representatives of people on terrorist watch lists. And yet for all its radical intent, the artists mute their own impact by inscribing their political work in the language of institutions, cutting off their own access to power by engaging with the art world’s enmeshed process of self-canonization as a conceptual gesture rather than a political act resulting in a concrete social agenda.

Jonas Staal’s “New World Summit” brought together leaders of unacknowledged states for a self-organized roundtable, disrupting an art venue with a political ready-made. Yet the action remained a performance rather than a political initiative; it gained acclaim on the territory of art by positing a political event as the zero-degree of art in an art institution, rather than by organizing a concrete political act. Achieving political change would require a continuous engagement with the procedural aspects of art production, whereas artists, even after identifying certain political problems, have to shift to a new piece to remain legible. A project like Staal’s draws attention to social problems but offers no political program to solve them; nor can the artist afford to make it his life’s occupation. In his 1989 paper “Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions,” Benjamin Buchloh offers an elaborate mapping of how the art world’s self-negation administers itself in such a way as to construct a set of provisions for transforming art institutions into their own permanent self-critique.

Such political agendas do nothing to encourage the desertion of the territory of art in favor of real political work. Political impact is valorized as the coefficient of art’s bureaucratic power to validate a social gesture (“nonart”) as “art.” This species of socially engaged art, in terms of validation by art’s bureaucratic apparatus, ends up closer to conceptual art than real social engagement. The aspiration for art to have social impact and be comprehensible to a broader public often remains wishful thinking. As a result, art discourse follows two opposing paths, doubting its capacity for democracy at the same time it pretends to incorporate public aspirations as an embodiment of direct democracy. Art remained alienated in form and content in an alienated society, and did nothing to hide its condition. In the wake of Debord and the Situationists, art’s social aspirations became more vivid and tangible, yet the social impact of this shift was confined to the cultural and institutional sphere, unlike the life-building projects of the early socialist avant-garde, which, due to the revolutionary refashioning of political economy, acquired governmental power. What Tall Can’s work captures is a community declaring its right to sovereignty, declaring through art a clear and straightforward message: el barrio no se vende.

Besides his photography, Tall Can also had on display the dice he made out of various pills while locked up. The pink are Tums and the blue are sleeping aids:

The gallery opened at noon and for some reason I thought we’d be running music all day. Instead the music started around 5:00 and I have to admit with this show capping off a week of other gigs and rehearsals I felt a bit like I had been asked to stay late at work on a Friday. Thankfully the bill was full of homies including Snapghost, Chieftain and Adrian aka Bourdain Cobain aka Bob aka tie.game.rivalry aka baby.brother aka terry k aka Rivalry aka YEAH BOB so the time went by quickly, especially once Tall Can jumped onstage to join Adrian for some Sister Schools tracks.

I’m usually ambivalent (at best) toward live band hip-hop, but when the opportunity arises to play with either Nathan or Tall Can I’ve learned never to say no. Nathan tends to produce a lot of piano-based beats which it was my job to translate to guitar, so I chose my old shitbox Squier Strat since I wanted both a whammy to abuse and a guitar I could throw around. I knew as soon as I started tossing out “Bad Horsie“-style whammy whinnies in a hip-hop band people would compare us to Rage Against the Machine but for my money we sounded much more like Limp Bizkit or the Sonic Youth/Cypress Hill collab from the Judgment Night soundtrack.

After the customary huarache from La Fachada I slumped home to review the various clips people had shared to Instagram, but the first post I saw was my digital tarot courtesy of Jason Byron, which felt especially fitting after a long week of rehearsing and gigging:

And we finally got our first review for pilostyles courtesy of Doth Music, who deemed the album “…undoubtedly one of the year’s most enjoyable rap projects. …quite visionary… It has an irresistible disjointedness to it that if it doesn’t have you hooked on the very first listen will have you considering a replay. …Intense!”

Oh, you still haven’t listened to it? What’s wrong with you?

Leave a Reply