I grew up with the piano, I learned its language while I learned to speak.

January 24th. Manfred drove you up from Lausanne to Cologne in his old Renault 4; neither of you slept and the car ride did no favors to the brace around your back, so by the time the hotel lobby congealed around you it was all you could do to prop upright in a corner, just watching the motion of people there as if it was an amoeba, an organism, under a microscope, and every now and then we started to giggle. We were sitting in complete silence and every now and then we’d giggle. The porter kept moving in the same pattern, but he had no real role… it was just a habit…

The promoter, some Vera Brandes, shows up late, but with word tonight’s show has sold out. Arrangements have already been made to record the performance but a full house does promise a certain electricity; even in your tired fog the news is enough to stir you from a momentary daze.

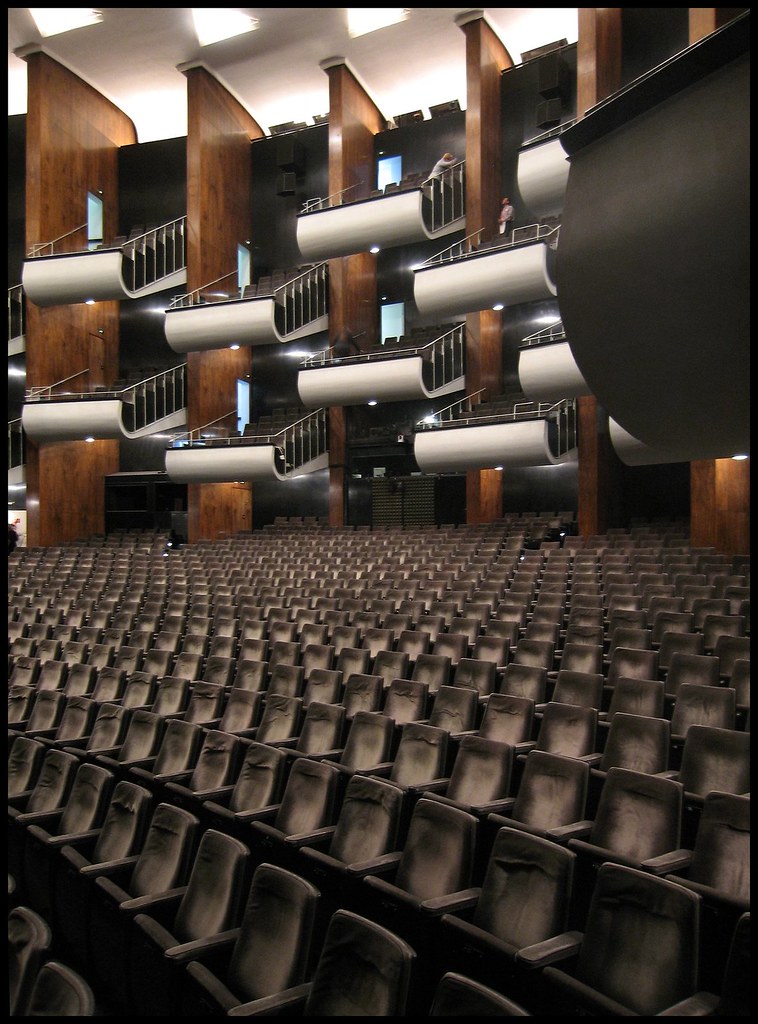

The venue is the Oper der Stadt Köln, taking a break from Wagner or some other Teutonic titan to host you in their first non-classical solo recital. That’s something of an achievement, right? Qualified or otherwise?

Gigantic bells peal out from the opera house, ringing a half-formed pentatonic idea: A—D—C—G—A.

Vera told you the hall was ready. She couldn’t have been more wrong. Of the two Bosendorfers in Cologne — how could there be not a single Steinway in Cologne? — the loading crew had, of course, brought the junker, a seven-foot instrument left untouched for God knows how long, sounding every bit a harpsichord or a barroom tack piano down to the loud, thumping pedal, and when you ask the loaders to switch it for the other Bosendorfer they dumbly stare and tell you the truck’s already gone. So get another truck, dammit, but none of them are big enough to carry a real Bosendorf, only this cheap garbage.

All the while the idiot sound crew sets up their microphones, probing inside the wretched instrument in search of the best position from which to capture its limp sonority and clanging, echoing pedal. More amoebas like the porter, moving through their same patterns out of habit.

Back at the hotel you try to sleep it off to no avail. The coarse, thin sheets grate against your skin and everywhere hum the sounds of a modern hotel filled with wires and silverware. You’re locked in a vibrating animal out of tune with yourself.

Finally Manfred comes knocking to take you to dinner, in the hottest Italian restaurant I’ve ever been in. Sweat drips off your brow to sting your eyes and somewhere in the back of your shirt a single droplet tickles your spine. Waiters bearing plates appear to distribute dishes between hoarse laughter and sloshing wine glasses. Dinner is served — with one notable exception. We were sitting with about ten people and everyone was served before I was. Surely there must be some ludicrous mistake. You assail any passing waiter in your search for the missing link in the chain. Your food will be right out, sir, they assure you. You remind them who you are, that you have only forty-five minutes before you must return to the hall for the night’s performance. A pause and a blank look of impatience, incomprehension or something between the two.

Your food will be right out, sir. Another amoeba.

Send them back, you order Manfred when you finally get back to the hall and find the recording crew. I don’t see any reason why they should stay.

Manfred, ever the archivist and entrepreneur, suggests they stay, if only to capture the struggle for posterity’s sake, well, what about having just a documentary of this… We know what we went through. We’ve paid for them to come here, so why don’t we just let them record it and we’ll just have a tape of it. Half of you wants to argue Manfred just wants to wring another record out of you and the other half is too tired to put up a fight this close to curtain call.

And so the crew stays. And so that’s how the Koln concert came to be recorded.

Backstage between bouts of nodding off in a tired stupor you slapbox with the engineer, half to vent your frustration at his presence and half in order to keep moving around. At least Manfred is there. He’s the only one I know who knows what a piano should sound like. Manfred, your steady companion; where were you before he joined your entourage? Lost without a contract thanks to Atlantic and George’s bungling. “The recording at Atlantic sold quite well,” George would try to reassure you, “but again it was hard to get US bookings for really good money because the market just wasn’t there. Times were getting rather bad for jazz… they were getting worse and worse… so Atlantic dropped the contract.” Off the strength of your appearances with Miles — or maybe just pity, you try not to think — Columbia signed you a mercy deal including a booking at their own Columbia Artists Management Hall. But even from that date you can hear George’s words reverberating through your skull: “He played one concert which may or may not have been completely solo, but it was a big flop” — as if no artist was ever permitted an off night — “and for this sparsely attended concert… I remember the promoters coming up to me and saying, ‘Gee! look at us — brutal exploiters of magical talents!’ and they laughed because they lost their shirts on the concert.” And so Columbia dropped you, too, for Herbie, another Miles alum. Plead as you might, George was past listening: “The attorney I used for the contract said, ‘Let’s sue them,’ but I said, ‘What will we get out of it?’” — how about the contract back, for starters? — “‘It’ll cost money and they’ll be bitter about it — they won’t do anything.’” They dropped me after two weeks. I had a twenty-page contract… I didn’t even have a letter saying that I wasn’t with them any more. I didn’t know that I’d been dropped.

But contracts don’t matter right now. Neither does the soggy Italian crap you shoveled down your sweaty gullet in that hothouse restaurant. The important thing at this moment is Manfred is behind you, Manfred who pushed you from the end of the Atlantic days to play these solo concerts, who bankrolled your finest performances, recorded or otherwise. Manfred who grants you the stage to enter the State of Grace. When I finally had to go out on stage to play it was a relief because there was nothing more of this story to tell. It was: I am now going out here with this piano — and the hell with everything else!

But of course stepping onstage is only the beginning of this story. I remember going out on the stage – and this is probably the important point – I was falling asleep. All I had to do was sit down and I’d be, not really falling asleep, but I was nodding and spacing out when you should be lasering in on the fact that we will not be unconscious on stage tonight. We will be conscious of playing this music. No room for autopilot like “My Ship” in Sardinia. Talking about not knowing what time it was. I swear that’s three minutes or so out of my life that I didn’t even live! And I looked up and in a split second they were looking back with the same kind of glazed expression on their faces. We took a break a few minutes later and went backstage. I said to them, “Man! If we ever do that again and don’t know it in three minutes, that’s going to be the end of playing!” …That was like a blackout! — having the power switched off and you’re still sitting there. There’s making space for the music to take you over, and then there’s whatever that was.

It was like a neutral thing — there was no impetus, there was no reason to be doing this music this evening for these people. No one listening knows where you’ve been or how you’ve struggled. I remember once hearing one of my younger brothers telling his girlfriend my story, what my career was like — I was born, I was talented, I got into piano, I had this neat place and I worked with Miles Davis. He left out this giant part which was the struggle! No one ever understands your struggle. Only Miles… In Miles’s band, before I joined, no one knew what he was trying to do… I think he knew that I did, which is why we had a good, close relationship. He said things to me I never heard anyone mention, just a very few words now and then about the music, but they were so meaningful — these were just times when we happened to be sitting together and the rest of the band wasn’t there… then, suddenly, the band changed. Jack Dejohnette had been in the band not too long, and then I joined, and then Michael Henderson joined. The whole feeling of the band changed a lot. It went from pseudo-intellectual shucking and ego tripping to a really healthy, round, bouncing band. And Miles, almost from the beginning of that period, rarely left the stage, he was up there playing incredibly much. People were amazed.

Miles understood. Most people haven’t seen the success I’ve had and they have an envious feeling about it. I would like to say to those people, “Enjoy whatever situation you’re in now because the pressures of being successful and still being an artist are greater than the pressures of not being successful and being an artist.” The limitations of the instrument, the venue, your own body — none of that matters to the music, to it. You’ve always faced challenges: in Miles’s band, it was that dry club sound… everything we did had a punch that it wouldn’t have in a concert situation. And it was just like it made the whole room vibrate — and I don’t mean loud — but the main thing was that Miles’s strength was… awesome there… and I’m using that word not in its modern sense but for what it really means. His playing was so strong. As far as I’m concerned there’s no document of that band at all. Jan Garbarek was in the audience the first week and he will attest to the same thing — that it was one of the most powerful musical things he has ever heard. Cheap instruments, poor sound, none of it matters. A truly valuable artist must be an artist who realizes the impossibility of his task — and then continues to do it.

Remember what Rilke wrote his friend in that letter: “Always at the commencement of work that first innocence must be re-achieved, you must return to that unsophisticated spot where the angel discovered you when he brought you the first binding message… If the angel deigns to come it will be because you have convinced him, not with tears, but with your humble resolve, to be always beginning, to be a beginner.” Ideally, I’d like to be the eternal novice, for then only the surprises would be endless. No one understands it, not the crowd, not the other musicians with whom you’ve shared the stage… there’s one thing that I know well — that I feel very alone. It’s the price you have to pay if you want to be yourself. And don’t believe that I don’t suffer for it, but it seems to me that I have nothing to say to the majority of people and it’s perhaps that which makes me feel timid… I’m very demonstrative when I play. I always make faces, laugh, jump about, gesticulate, and am very animated, and many people who see me like that think that I’m much more reserved when I’ve left my piano. In reality, I feel truly at ease only in music…

Those bells ring again, A—D—C—G—A. Time to move.

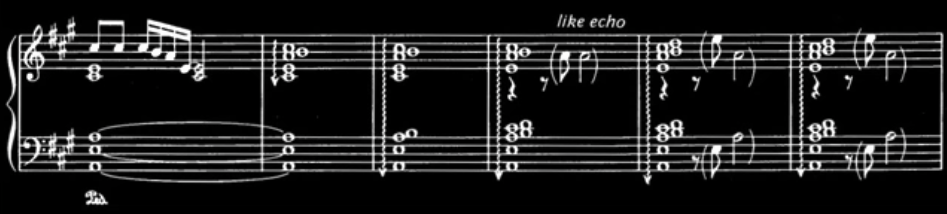

The Bosendorfer’s lower registers are just barely acceptable, but anytime you venture past middle C the tone becomes harsh and abrasive. So you keep to the center:

Inspiration can come from the strangest places; the audience catches your little riff on the opera house’s bell theme before you’re even aware you’ve played it. Nervous titters through the hall.

But it’s a nice little melody; some longing lilt inhabits the bell motif, some touch of the romanticism you so often chase — remember what Jack said, “the fact is that romanticism is something that’s missing from a lot of the music. We do need romanticism and we also need some compassion.” And in just seconds you’ve found it, tonight’s theme, the base materials you’ll expand outward in every direction: three eighth notes offset by a little semiquaver bounce. Begin the process of variation, shifting keys under the motif, modulating by way of an E minor 7 to a D major, back to F on your way to G, building up to that lift on the IV ferrying you right back to A minor. The theme insists, pressing itself into every corner of the music:

Crescendo in that Bosendorfer’s thick low end, layering dense pop voicings. Keep going, keep reaching—

And there’s that tinny high register again, piercing the dense, rumbling crescendo in the bass. Did that sound intentional? Could the audience see it coming? Take it back to A minor. Lay off the pedal and it rattles through the whole piano. Jesus, every mistake tonight is amplified. And recorded! Throw some chromatic flash to make them forget, but comfort is an illusion and you find yourself right back in that piercing treble range:

Walk it back, give them some of that warm, throaty midrange: that’s the spot. You could make this a home for a while. Lay in some ostinato figures:

Christ, how long have you been playing these Phrygian riffs? Is the audience getting bored? It’s like Sardinia all over, like you’re another one of the amoebas executing a programmed pattern. Jesus, don’t lose track. What was that little theme you had again?

Was that it, was that how it went? You’re losing sight of it. Listen for the spirit. The Bosendorfer’s thin upper range is a killer, but when the State of Grace overtakes you, the temptation to fly is irresistible. If I don’t manage to fly, someone else will. The spirit wants only that there be flying. As for who happens to do it, in that he has only a passing interest. And so you expand your tessitura even as the Bosendorfer’s tone grows tinny:

I know that when you’re an improviser, a true improviser, you have to be familiar with ecstasy, otherwise you don’t connect with music. When you’re a composer, you can wait for those moments, you know, whenever. They might not be here today. But when you’re an improviser, at eight o’clock tonight, for example, you have to be so familiar with that state that you can almost bring it on. And bring it on you do, just like that night Forget again the limitations of the instrument and let yourself fly. The spirit wants it, demands it. Improvisation is really the deepest way to deal with moment-by-moment reality in music. There is no deeper way, personally deeper.

You have to be completely merciless with yourself. It’s been your mantra since you were a child, but you find yourself returning to the idea as you splay your fingers to span broad octaves. I was so bad with parallel octaves. If I had to play sixteenth notes in octaves or scale sixths — I can’t stretch that far! So I more or less had to bully myself into being able to play those things! So what if you weren’t born a Liszt or a Rachmaninoff? Some of it is magic and just desiring to play it!

And those octaves always held a special magic for you. Remember back to when Charles Lloyd was on a Gurdjieff kick — yet another of his pseudo-spiritual hippie affectations — and his copy of All and Everything was given its own seat on the plane. You flipped through to that chapter on music. Or art? Was it Gurdjieff after all or Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous? Doesn’t matter. What matters is what it said about octaves was so simply, exactly what was true about an octave and so basic, yet I had been alive for twenty years and no one had mentioned this thing. Universal vibrations divided into degrees of density, the Universe as a whole resonating in an infinite array of unique frequencies, and somewhere within that limitless range lie not just the frequencies you play but the ones you inhabit, the forces flowing through your being and tuning entire stadiums to your resonance, the music just one minuscule aspect of a greater whole… What I’m saying is, I guess my calling isn’t even music to me, it’s it, whatever it is… Sometimes I can feel it, and as an accomplished player I can feel it and not be embarrassed to attempt to play it, and not be uncomfortable and not be afraid. And yet I know very, very well that it can never be played, and it can never be written and it can never be read off a page… and what it is, is a sublimation of a feeling we originally had, that we wish we could convey without this intermediate step.

It all comes back to Gurdjieff. I can tell you truthfully, I don’t know what I thought about before that day. I have no idea what was in my head… I can trace back to that day the involvement in what I consider a deeper and deeper process. First it was a process of being into this man and then it was a process of being into this man’s work, then it was a process of being into the work’s relationship to other work, and then of seeing that there was a work greater than that, that was really responsible for all that… and that brought me to Sufism… Then the Sufism fell away too, because my wisdom in my work doesn’t need to be given little jolts by writings of certain philosophers. Your wisdom doesn’t even need sound to verbalize itself, to bring itself into being. I have a feeling when I start to play that would be completely sufficient without the music… When I was with Charles Lloyd at the end, there was a time when we were playing all these E minor vamps and I was playing sometimes one note for a while and I realized that one note says it all, really, it does. I would have been content to continue playing that note till my fingers dropped off.

That asshole Lloyd. He used to blather, sitting in the lotus posture in the midst of a group of reverential university students, in his usual role as guru, and Jack and I were there reluctantly: “I play love vibrations, love, totality — like bringing everyone together in a joyous dance.” But “bringing everyone together” was about where his concern ended. Jack was right: “We put our all into that band — everybody — and we didn’t make that much money,” especially with George breathing down your necks over every expense. We’d always owe him something… coming back from this horrendous trip, where we were lucky to be able to play good music that we enjoyed a couple of times, we all either owed something or we’d see that the personal Kleenex pack we’d borrowed from him was listed there. “Well, we had to buy wine for the Russians,” he’d whine, “they were so wonderful we bought them some wine and we’re all sharing the expense… and remember, you didn’t have any film and I said I had plenty and I gave you a couple of rolls of film…” Meanwhile Lloyd buys himself another fur coat and makes you borrow Chico Hamilton’s car to spin out somewhere in the Arizona desert while he flies himself to the next gig.

“Keith was not the kind of person that would help you musically,” Ron used to say as if it was an accusation. “He wouldn’t show you the changes to a tune if you didn’t know them… he wasn’t a team player, wasn’t supportive… he was never really one-of-the-boys, he never had that experience in his life, I’m sure… he’d never played baseball…” Not true. I was into sports too. I was good at stealing basketballs, good at baseball and pitching, good at ping-pong and even football; I was even wrestling for a while. At least Ron understood one thing: “Keith’s a genius. He’s so far ahead of most people… you know, those guys are not easy to get along with…”

Forget it. Remember what you’re doing here. Lloyd was right about one thing: yours is a holy calling. If I could call everything I did ‘Hymn,’ it would be appropriate because that’s what they are when they’re correct.

You can’t get lost in your head like this. Play to your strengths: those close voicings and overlapping notes only your delicate fingers could articulate…

…but never allow yourself to get lost. Remind yourself at every moment of your surroundings. You have to be completely merciless with yourself. You can never forget that, can never let that autopilot take you over and turn you into another amoeba. Find the shape inside the sound…

…tease it out…

…give them something real, something to grasp. You’re never in a secure position. You’re never at a point where you have it all sewn up. You have to choose to be secure like a stone, or insecure but able to flow. The choice is yours in every moment but you may never let the audience glimpse the process, even while they watch it unfold in front of them. When I improvise it is exactly the same process as my composing, taken to a million, zillion, times faster speed. It would be like a chess master playing, making a move every second or so, but the processes for me are the same. For someone else who improvised and composed they would be totally different because his improvisation would be coming off the top of his head whereas mine is not. That’s why I get more tired legs than hands when I play because of crawling all over the place trying to get stuff out.

They make fun of you for your crawling and cries. A critic in the presence of genius can only perceive “his autoerotic groans, sighs, grunts, and moans as he leaps from his chair to thrust his pelvis at the keyboard while he plays.” Those are very high moments in the process of playing. They’re not always high moments musically. Only Jack came close to understanding what he called your “love affair with the piano,” but even Jack couldn’t see this was bigger than some cheap romance: Improvisation is more than the word expresses. It is a greater responsibility… in that the participation with the moment is, hopefully, complete. It is a “blazing forth” of a “Divine Will” (Divine if only because of its greater force). This means that you (the pianist) are not only a victim of a message (impulse) quite beyond your own human ideas and thoughts, but you must put out (into the world of sound) as large a portion of it as possible (first having put complete trust in the “impulse”).

A musician can trust the notes that come out, or he can trust the feelings that go into the notes that come out. He can’t trust both at the same time, because never do they equal each other. There are innumerable examples where I know that what was to be heard was too much to be played. And I don’t mean that I needed extra hands or another pianist or a band or something. And I’ve known that since I was young… and I’ve felt that for myself for so many years. I believe that a truly valuable artist must be an artist who realizes the impossibility of his task… and then continues to do it. Like your early records playing solo, when the State of Grace lay tantalizingly close yet just out of grasp. I wasn’t as good a player as I am now… It’s not that I’m putting them down, it’s just that I hear nothing but what’s wrong with them. I can see and hear what was going on and the magic… but I know that magic’s existing anyway, so I’m saying, “Gee, why didn’t I just let the magic be there — why did I have to get so… whatever it was”… because sometimes it’s so crucial not to play. So there’d be times when I listened to an old album and I’d say, “Why did I play those notes?” I can tell when those notes were demanding to be played or not… Everything I’ve done so far is a series of failures, and if you tie that up with how I was talking about the “it” in music, then my statement does make some kind of sense. I can live with the fact that they’re failures, because I can see the great effort being made… even in the old things… I’m not saying I’m sorry I made those albums. I’m just saying that, as I am now, listening to them gives me certain experience which is mostly of what I didn’t do, or what I did too much of.

Is that applause? Was that the encore?

Where have you been?

Offstage the usual gang of reporters and sycophants await to harangue you for comment on who-cares-what. “When somebody praises you,” Mom used to instruct you, “you send the praise back through you to the Creator!” Then again, she was a nurse who never believed in medicine. Worst backstage are the fans who have somehow found their way into the wings, and worst among them are the would-be-superstars, the wannabes aching for a chance to graze genius. Like that one loser who couldn’t even make up his mind on whether he’d be a dilettante on guitar or piano. He told me all this stuff and I said to him: “No, man, you should just keep playing… don’t let it get you like that. Just do it!” This is what happened from that casual encouragement, and it’s one of the most revelatory things that I ever remember happening casually between me and anyone else. He made an album on piano — anybody can make an album in California. He sent it to me saying, “You really were so encouraging and I’m really into it now and I did this album, and I want you to hear it. Please let me know what you think.” Well, the album was so bad, it was not just neutral music, it was blown up — the liner notes making it out to be something it didn’t have any right to be. Now he’s asking me to get back to him about it, and I’m the one that encouraged him to do this! So I wrote him a letter saying: “Really, this is garbage. Whatever I said, I know I said, but you want a response about this music and you want my opinion and that’s how I feel and I’m not going to change my mind about it tomorrow.” He now carries that letter around with him and he’s made me into the devil. Retribution for him is to have the letter with him, but to believe nothing that I say is true! …To me that experience damaged a process that I would like to see happening — the process of being simply encouraging without being a power who is encouraging. He probably took my encouragement as a mandate. Should have squashed the amoeba right away…

Margot used to ask me why I was so cold to people backstage. I was never cold, that was her perception of it, but there’s a very good reason for being not even distant, but so clear that it feels like needles. After a concert no one should ask me a question. I’m more clear after a concert than at any other time. People come backstage and ask me what I think of so-and-so’s record or music. I say “Terrible!” and they’re shocked. My clarity is up and down like everybody’s, but after an improvised concert when I’ve made fifty million possible small decisions, my reactions and speed of thought are, like, getting in shape. It’s like running five miles and somebody says, “Gee, you ought to be tired!” But no — now I’m ready to run. To fly.

In the car some time later Manfred will play the cassette from Cologne and decry first the piano’s sound, then your repetitive ostinati: “It’s a little bit towards this minimalist thing — Glass and Reich, etc… maybe the lack of technical substance,” but of course the record executive in him wants to put it out anyway. It’s been said that Manfred is too lenient with me… and people wonder why there isn’t some constraint put on what I release… because then you could just release the good things. No one ever seems to pick up on the dynamic. The funny thing is — over and over again, Manfred’s the one who suggests releasing the whole thing! It’s never my suggestion. We were looking for the one good concert that we felt was outstanding in Japan. And what happened was, our letters crossed in the mail. My letter to him was saying, “I’ve narrowed it down to five, but I can’t choose between them.” And his letter to me was saying, “I think we’re going to have to release a multi-record set.”

“That’s how I see it as a producer and publisher,” he explains, “to go along with people whose creativity is clear to me and, whether every album is a statement for history or not, I don’t care. I care whether it’s a statement for the musician to be able to get something out of his mind and go further.” So naturally he doesn’t need any convincing on the release front, but his barbs about your performance sting nonetheless.

Sleep-deprived again on yet another long drive across Europe, you try to explain that there is a logic people associate with reality that reality doesn’t actually have all the time, but which did exist on the occasion of that particular concert. You can feel his interest waning. There’s a logic to the music in that concert — it sounds free, but it also sounds like it’s moving from one thought to another without any separation, without any jump. Yet reality is more a series of jumps than that steady stream of thought being nice and smooth… I think of that album as being full of really rich ideas but describing not as much of the process as I’m interested in describing… very much less describing the process than the other live solo recordings.

But processes and patterns don’t make a hymn. Whatever it is, it’s not that. Well, there’s one of the things — it has to mean a lot. If you play a note, it’s got to mean something.

Leave a Reply