Spring has come. Perhaps there are sulla blossoms in the country. Here in the city is sun, and more rain than is really necessary. It cannot matter, can it? Even I suspect the growth of our child has nothing to do with time. Her name-wind will be here again; to soothe her face which is always dirty. Is it a world anyone could have brought a child into?

Thomas Pynchon, V.

Is it a world anyone could have brought a child into? Reviewing Against the Day for the NYT, Michiko Kakutani contended “[f]or all its razzle-dazzle brilliance, Mr. Pynchon’s earlier work tended to be cold, hard and despairing: devoid of any real sense of human connection, soulfulness or redemption. That began to change with his 1990 novel Vineland, which evinced a new interest in an individual’s relationship to family, and with Mason & Dixon, which made its heroes’ longings and dreams as palpable as their comic high jinks.” Yes and no. Vineland features some of Pynchon’s deepest meditations on family, both in the form of extended histories (such as those of Frenesi’s parents) and found family reunions (the ending scene where the entire Gates-Wheeler[-Fletcher] clan, live or Thanatoid, including dogs, finally overlap at a party is maybe the most sentimental in all of Pynchon’s work — runners-up including Mason & Dixon‘s intercalary melancholy or Doc Sportello’s nostalgic waxings in Inherent Vice, both from the latter half of his publishing career) while at the same time concerning itself with the dissection of systems which so thoroughly preoccupies his first three novels.

Is it a world anyone could have brought a child into? “But the line on Pynchon’s inhuman and character-lite coldness,” according to Peter Coviello’s excellent little Vineland Reread, “does more than rehearse, in a slightly statelier key, those many disquisitions on character and ‘relatability’ familiar now to readers from message-board commentaries, Goodreads, and the Amazon reviews page.” Coviello takes Kakutani — who for what it’s worth has frequently gone on record praising Pynchon — to task in the same manner in which Edmond Caldwell (RIP) used to regularly eviscerate James Wood. “In certain senses,” Coviello writes, Kakutani’s take on Pynchon’s supposedly cold, hard and despairing earlier work

is fair enough. If you go to Pynchon looking in this way for the aesthetic machinery of the nineteenth-century novel, even as remixed toward ironizing complication by a variety of postmodern flourishes, you will likely emerge disappointed and maybe even aggravated. This is patently not, however, because Pynchon has no regard for the aesthetic machinery of the nineteenth-century novel or, for that matter, for the specific technologies of character that come to a certain kind of fruition there. The person who names one of his narrators “Wicks Cherrycoke,” I think we can agree, is not a writer whose affection for a history of the novel that would run through, say, Dickens is much in dispute. (Or Rex Snuvvle, or Shasta Fay Hepworth, or Tantivy Mucker-Maffick…)

“The identification of the novel with the thick interiorization effects I’ve described,” Coviello continues, “makes for a very poor reading of novelistic character.”

Even in its maximally psychologized, most hegemonically “realist” modes, novels proliferate several kinds of character and can’t be reduced to just the one. The simplest way to say this is perhaps to note that not everyone is Dorothea Brooke, not even within Middlemarch. Even if we were to bracket the long histories of novelistic character, which would necessarily include a more serious consideration of the complexly “flat” character of eighteenth-century fiction, and even if we conceded for the sake of argument this naturalization of “the novel” in its ripe realist mode, still the picture that emerges is not remotely so uniform. Dickens, that obvious Pynchon forebearer, is perhaps the most illustrative example. To sit down with Bleak House is indeed to encounter figures of great “psychological depth,” in Kakutani’s terms, like Lord and Lady Dedlock, the wards of Jarndyce, the lawyer Tulkinghorn, even the indelible Krook. But it is to venture too into a world given substance and shape by innumerable fictive persons manifestly not deployed for purposes of interiorization, psychological portraiture, or any sort of bildungesque evolution. The thronging and textured Dickensian world functionally is that panoply of variously inflected types, circulating in vivifying relation to figures offered at different scales of psychological characterization. These “minor characters,” as a scholar like Alex Woloch reminds us, are entirely of and in the tradition of the novel and are indeed among the most elemental grammars of its construction. Which is only one, considerably less irritated way of thinking about Pynchon’s abundant affection for them.

This is all clear enough. (Kakutani might well respond: Pynchon could use more Lady Dedlock, less Guppy.) But there is a further and I think graver misapprehension involved in taking Pynchon to be a novelist who keeps loving the novel and, in his weaker seasons, failing at it, failing to hit its marks or to live up to its most winning protocols. All I would wish to say on this score is that Pynchon’s love of the novel… does not work like that. (In a book of criticism such as this one, entailed in extended consideration of the kinds of effectivities that might follow from the love of certain sorts of object, this seems a point especially worth insisting on.) That love is not imitative or replicative, is not an Eliotic extrusion of individual talent into the reach of tradition or a Bloomian struggle against Oedipally menacing forebearers. Nor again, I would insist, is it a matter of irony, reversal, parody in the many registers we have been taught to recognize as postmodern. What transpires in the charged space of Pynchon’s regard for the thing hypostasized as “the novel” is weirder, and denser, and, for our purposes, greatly more edifying.

Is it a world anyone could have brought a child into? Anyway, all this to say the family talk, be it weird or dense or edifying, is nothing new in Pynchon’s fiction, going all the way back to V.

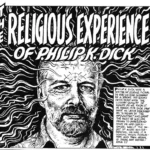

Is it a world anyone could have brought a child into? Hitting a little close to home there, TP, if we’re ready to get a touch more personal: The Crying of Lot 49 was one of the first “real” books I read on my own, borrowed alongside A Scanner Darkly from the library after reading both were influential on whatever cyberpunk swill I was chugging elsewhere. Chalk it up to early exposure, but no artist’s work has grown with me like Pynchon and PKD’s, and every time I revisit a book from either one I find deeper resonances, strange parallels, entropic synchronicities… or maybe reading those two as a preteen programmed my paranoia as an overdetermined system. The world may never know!

Leave a Reply