𝖑𝖊𝖆𝖛𝖊 𝖙𝖍𝖊𝖘𝖊 𝖔𝖑𝖉 𝖑𝖔𝖓𝖊𝖑𝖞 𝖇𝖔𝖓𝖊𝖘 𝖚𝖕 𝖔𝖓 𝖙𝖊𝖑𝖊𝖕𝖍𝖔𝖓𝖊 𝖜𝖎𝖗𝖊𝖘

𝖈𝖔𝖓𝖛𝖊𝖗𝖘𝖊 𝖜𝖎𝖙𝖍 𝖜𝖍𝖎𝖈𝖍𝖊𝖛𝖊𝖗 𝖉𝖊𝖒𝖔𝖓𝖘 𝖞𝖔𝖚𝖗 𝖍𝖊𝖆𝖗𝖙 𝖉𝖊𝖘𝖎𝖗𝖊𝖘

𝖑𝖊𝖙’𝖘 𝖘𝖊𝖙 𝖙𝖍𝖊 𝖕𝖎𝖌𝖘 𝖔𝖓 𝖋𝖎𝖗𝖊

It’s amazing how little time changes things. Tall Can and I recorded this album six years ago, with the country in the midst of an authoritarian power grab amid nationwide protests while colonialist war raged in Gaza and global debt soared to record highs.

Then Tall Can got locked up. And a few years, a global pandemic and a prison sentence later, he’s been released into a world which… well, doesn’t look a whole lot different. Which is terrible for the state of the world, but does mean the rage against the powers that be contained in these songs feels as relevant as ever, even six years later.

Adorno asserted that if art cannot concern itself with truth (and before modernism, did so through sensuousness), it has to face its own inability and occupy itself with the absence of truth. Since the Romantics, art has presupposed the radical loss of truth. Under modernism, art distanced itself from aesthetic experience and moved closer to concepts, speculation, and theory without literally transforming into philosophy. Ultimately, with modernism, and further still through the avant-garde (both in the 1920s and the 1960s), art tended to negate itself as action and to historicize this negation, reestablishing itself through this self-emptying.

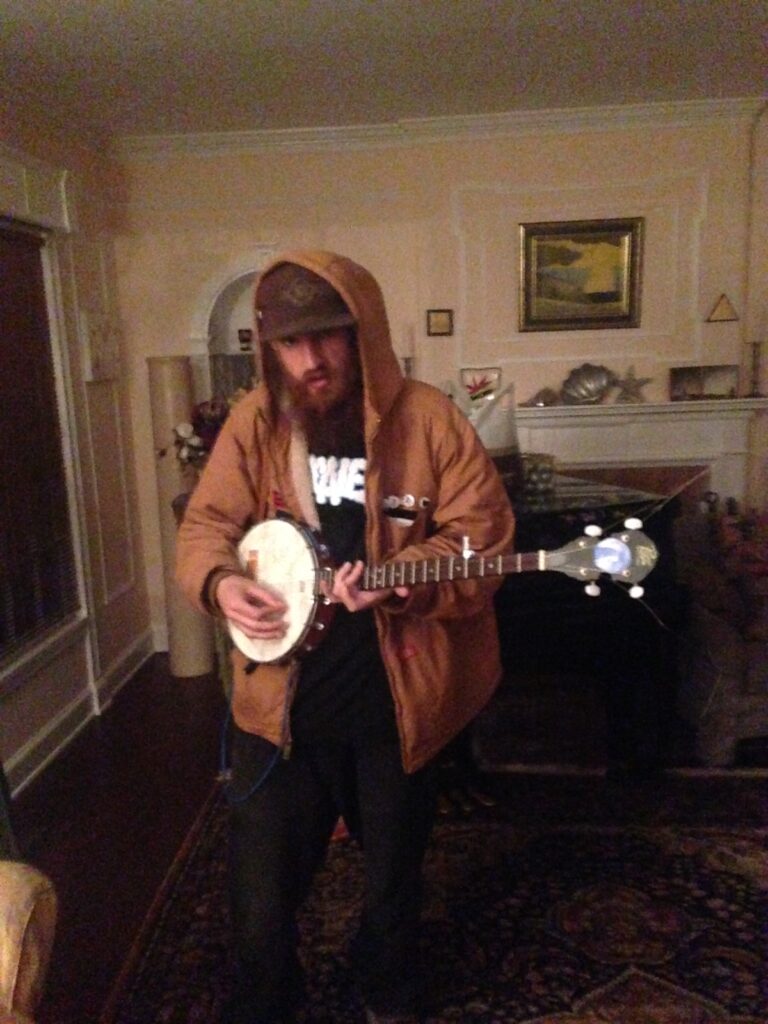

But lest my Adorno namechecks and apocalyptic doomsaying give you the wrong impression, this record is a deeply and unabshedly fun listen, bridging everything from east Asian surf rock and BBC interstitials to psychedelic soul and advertising jingles. The only guest is my beloved Maine Coon cat Monty. Tall Can and I started making music together in 2018, beginning with a few Those Darn Gnomes tracks. He’d show up to my house, we’d share whatever music we were into at that moment and I’d start making a beat while he wrote or simply freestyled and by the end of every session we had another couple songs finished. An air of free experimentation permeated those sessions, with Tall Can always ready to run his vocals through a new set of effects pedals (“food stamps from a faraway stargate”) or call for a guitar solo on a track (“if i couldn’t find the telephone”). This is easily the only hip-hop record I know of to heavily feature no-input mixing (“dracula”).

At the beginning of the 20th century, the negation of art revealed itself differently in capitalist and postcapitalist societies. Capitalist conditions inevitably lead to the utmost autonomy of art, to the point even social engagement spins around the realm of art and its self-reflection. In the early revolutionary conditions of the Soviet socialist state, the negation of art implied both an expanded socialization of art practice and a constructive convergence of life, labor, culture, and science. In the first case, art evolved under capitalism as radical negativity verging on nihilism, discarding previous forms, rejecting historical continuity, theorizing itself, and abstaining from social engagement. In the second case, conversely, art’s negation was intended to give rise to a collaboration between artists and the masses, in a joint creative project of rebuilding society, a radical disentanglement from aesthetics as futurological collective production, erasing the boundaries demarcating professional art as an exceptional practice. Under revolutionary conditions, the conceptualization and abstraction of art did not serve to detach it from the social realm, but to redesign it as a platform for social engineering. Abstract structure became a constructivist tool and a device for inclusiveness. The legacy of leading avant-garde theorists, artists, and activists like Boris Arvatov, Sergey Tretyakov, and Alexey Gastev confirms it: for avant-garde activists the material to work with and transform was no longer merely an artistic medium but the social environment itself. This broad socialization undertaken by avant-garde artists was possible precisely under noncapitalist conditions because works of art did not strive to fix social alienation or fixate on critiquing past art; they sought to expand into the infrastructure of mutual social work. Artists from the LEF to Andrey Platonov saw the redundancy of art as an exclusive aesthetic practice in a society understood in its totality as a creative, life-building project. Or as Tall Can puts it himself on “cactus jack”:

𝖎𝖋 𝖜𝖊 𝖆𝖗𝖊 𝖑𝖎𝖛𝖎𝖓𝖌 𝖎𝖓 𝖆 𝖗𝖊𝖆𝖑𝖒 𝖙𝖍𝖆𝖙 𝖎𝖘 𝖘𝖔 𝖙𝖗𝖚𝖑𝖞 𝖌𝖔𝖑𝖉𝖊𝖓

𝖜𝖊 𝖘𝖍𝖔𝖚𝖑𝖉 𝖙𝖗𝖊𝖆𝖙 𝖊𝖆𝖈𝖍 𝖔𝖙𝖍𝖊𝖗 𝖆𝖘 𝖘𝖚𝖈𝖍

𝖗𝖊𝖒𝖆𝖎𝖓 𝖍𝖚𝖒𝖇𝖑𝖊 𝖘𝖙𝖆𝖞 𝖔𝖕𝖊𝖓

𝖊𝖆𝖘𝖎𝖊𝖗 𝖘𝖆𝖎𝖉 𝖙𝖍𝖆𝖓 𝖘𝖕𝖔𝖐𝖊𝖓

𝖍𝖆𝖗𝖉𝖊𝖗 𝖕𝖑𝖆𝖈𝖊𝖉 𝖎𝖓𝖙𝖔 𝖆𝖈𝖙𝖎𝖔𝖓

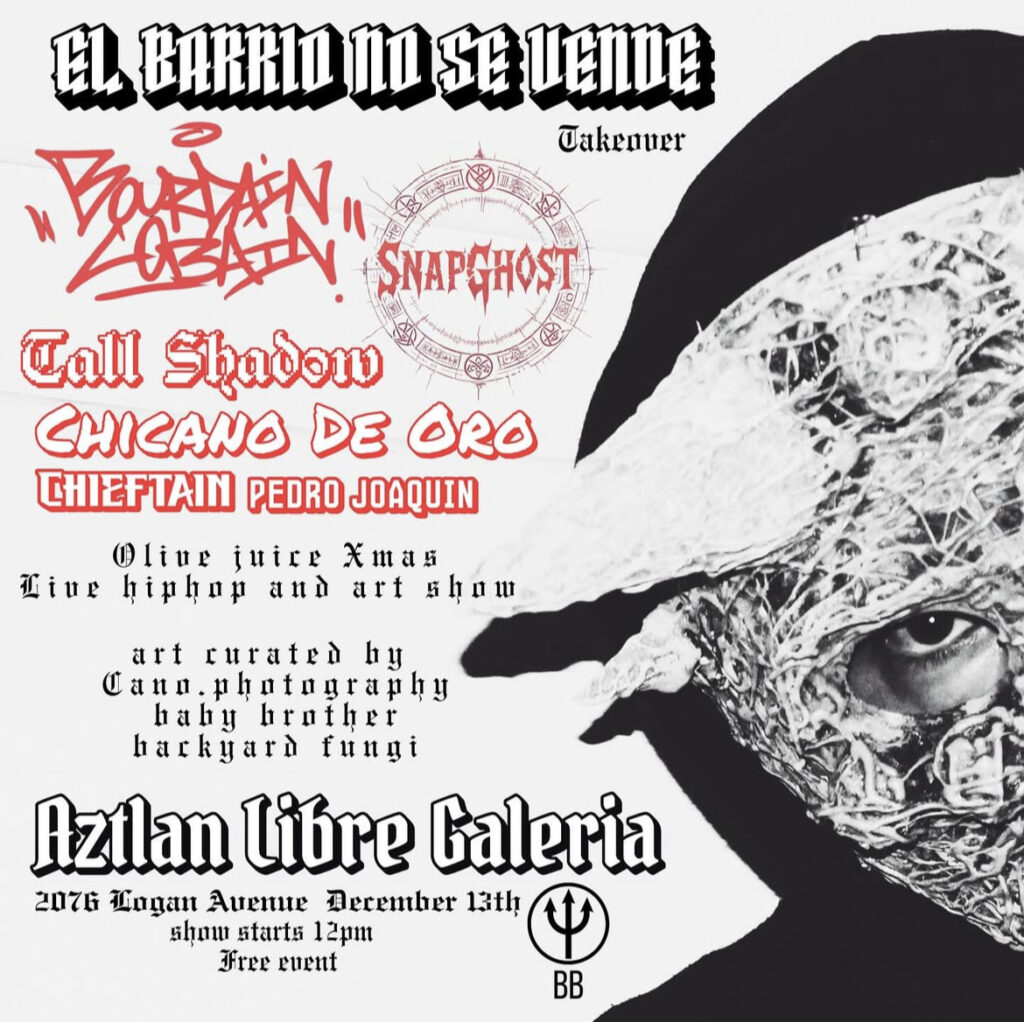

We won’t play anything from this album, but you can catch Tall Can and I with Nathan playing as tall:shadow next Saturday at Aztlan Libre, where his photography of Chicano Park’s murals will also be on display:

[On an internal note: this is the 200th post on this blog and finally closes the Purple Wave series of albums begun all the way back in 2019 with Patrick’s first album as Sword2Saber. Once you play through pilostyles wilflower, how about a walk down memory lane?]

Leave a Reply